Abstract

Background: Angiogenesis inhibitor agents have been shown to be effective in increasing progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC); however, these treatments have different toxicity profiles. Objective: Our objective was to quantify patients’ benefit-risk preferences for RCC treatments and relative importance of attributes in a common metric.

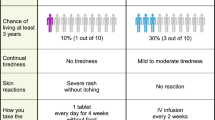

Methods: US residents aged ≥18 years with RCC completed a web-enabled, choice-format conjoint survey that presented a series of 12 trade-off questions, each including a pair of hypothetical RCC treatment profiles. Each profile was defined by efficacy (PFS, when overall survival held constant), tolerability effects (fatigue/tiredness, diarrhoea, hand-foot syndrome [HFS], mouth sores) and serious adverse events (liver failure, blood clot). Trade-off questions were based on a predetermined experimental design with known statistical properties. Random-parameters logit was used to analyse the data.

Results: A total of 138 patients completed the survey. PFS was the most important attribute for patients over the range of levels included in the survey, while remaining attributes were ranked in decreasing order of importance: fatigue/tiredness, diarrhoea, liver failure, HFS, blood clot and mouth sores. In order to increase PFS by 11 months, patients would be willing to accept a maximum level of absolute blood clot risk of 3.1%(95%CI 1.5, 5.3) or liver failure risk of 2.0% (95% CI 1.0, 3.3).

Conclusion: A 22-month change in PFS was shown to be the most important improvement for patients. Severe fatigue/tiredness and diarrhoea were rated as the most troublesome tolerability effects of RCC treatment. Patients were likely willing to accept significant treatment-related risks of 2–3% for liver failure and blood clot to increase PFS by 11 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

1 HFS results in the skin in the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet becoming tender or red.

References

Flanigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2003; 4 (5): 385–90

Lane BR, Kattan MW. Predicting outcomes in renal cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol 2005; 15 (5): 289–97

Klatte T, Pantuck AJ, Kleid MD, et al. Understanding the natural biology of kidney cancer: implications for targeted cancer therapy. Rev Urol 2007; 9 (2): 47–56

Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, et al. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden ofmetastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 2008; 34 (3): 193–205

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets [online]. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html [Accessed 2010 Aug 3]

Porta C, Paglino C, Imarisio I, et al. Cytokine-based immunotherapy for advanced kidney cancer: past results and future perspectives in the era of molecularly targeted agents. Scientific World Journal 2007 Apr 9; 7: 837–49

Bukowski RM. Cytokine combinations: therapeutic use in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol 2000; 27 (2): 204–12

Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J. Effect of cytokine therapy on survival for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18 (9): 1928–35

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (2): 115–24

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27 (22): 3584–90

Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (22): 2271–81

Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007; 370 (9605): 2103–11

Escudier B, Bellmunt J, Négrier S, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (AVOREN): final analysis of overall survival. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28 (13): 2144–50

Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (2): 125–34

Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27 (20): 3312–8

Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J ClinOncol 2010 Feb; 28 (6): 1061–8

Bridges JFP, Kinter ET, Kidane L, et al. Things are looking up since we started listening to patients: trends in the application of conjoint analysis in health 1982-2007. Patient 2008; 1 (4): 273–82

Louviere J, Swait J, Hensher D. Introduction to stated preference models and methods. In: Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD, editors. Stated choice methods: analysis and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 20–33

Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Mansfield C, et al. Crohn’s disease patients’ risk-benefit preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology 2007 Sep; 133 (3): 769–79

Johnson FR, Banzhaf M, Desvousges W. Willingness to pay for improved respiratory and cardiovascular health: a multiple-format stated-preference approach. Health Econ 2000 Jun; 9 (4): 295–317

Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments. In: Fayers P, Hays R, editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials: methods and practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005: 431–44

Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Watson ME, et al. Benefits, risks, and uncertainty: preferences of antiretroviral-naäve African Americans for HIV treatments. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009 Jan; 23 (1): 29–34

Lipkus IM, Hollands JG. The visual communication of risk. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1999; 25: 149–63

Krupnick A, Alberini A, Cropper M, et al. Age, health and the willingness to pay for mortality risk reductions: a contingent valuation survey of Ontario residents. J Risk Uncertainty 2002; 24 (2): 161–86

Huber J, Zwerina K. The importance of utility balance in efficient choice designs. J Marketing Res 1996; 33: 307–17

Kanninen B. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Marketing Res 2002; 39: 214–27

Dey A. Orthogonal fractional factorial designs. New York: Halstead Press, 1985

Train K. Mixed logit. In: Train K. Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003: 139–54

Train K, Sonnier G. Mixed logit with bounded distributions of correlated partworths. In: Scarpa R, Alberini A, editors. Applications of simulation methods in environmental and resource economics. Dordrecht: Springer, 2005: 117–34

Bryan S, Buxton M, Sheldon R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for the investigation of knee injuries: an investigation of preferences. Health Econ 1998 Nov; 7 (7): 595–604

Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ 2000 Jun; 320 (7248): 1530–3

Mantovani G, Monzini MS, Mannucci PM, et al. Differences between patients’, physicians’ and pharmacists’ preferences for treatment products in haemophilia: a discrete choice experiment. Haemophilia 2005 Nov; 11 (6): 589–97

Lee WC, Joshi AV, Woolford S, et al. Physicians’ preferences towards coagulation factor concentrates in the treatment of haemophilia with inhibitors: a discrete choice experiment. Haemophilia 2008 May; 14 (3): 454–65

Acknowledgements

A. Brett Hauber and Ateesha Mohamed are employees of RTI Health Solutions. RTI Health Solutions received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Inc. (GSK), Collegeville, PA, USA to complete this study. Maureen P. Neary is an employee of, and has stock ownership in, GSK.

As the supervisor for the study, Ateesha Mohamed takes full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors would like to thank the Kidney Cancer Association for their assistance in locating patients with RCC who may be interested in participating in this study and the patients who chose to participate in either the pilot study or the main study. The authors would also like to thank Christopher J. Abissi, MD, for clinical advice in construction of the attribute definitions and in the overall study design, and Reed Johnson, PhD, for advice relative to his expertise in benefit-risk methodologies for the study design and interpretation of results. The authors would also like to thank Vikram Kilambi, Ryan Ziemiecki and Lauren Donnalley for their assistance in analysing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, A.F., Hauber, A.B. & Neary, M.P. Patient Benefit-Risk Preferences for Targeted Agents in the Treatment of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pharmacoeconomics 29, 977–988 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11593370-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11593370-000000000-00000