Abstract

Prostate cancer is the most frequently non-skin cancer diagnosed among men. Diagnosis, a significant burden, generates many challenges which impact on emotional adjustment and so warrants further investigation. Most studies to date however, have been carried out at or post treatment with an emphasis on functional quality of life outcomes. Men recently diagnosed with localised prostate cancer (N = 89) attending a Rapid Access Prostate Clinic to discuss treatment options completed self report questionnaires on stress, self-efficacy and mood. Information on age and disease status was gathered from hospital records. Self-efficacy and stress together explained more than half of the variance on anxiety and depression. Self-efficacy explained variance on all 6 emotional domains of the POMS (ranging from 5–25%) with high scores linked to good emotional adjustment. Perceived global and cancer specific stress also explained variance on the 6 emotional domains of the POMS (8–31%) with high stress linked to poor mood. These findings extend understanding of the role of efficacy beliefs and stress appraisal in predicting emotional adjustment in men at diagnosis and identify those at risk for poor adaptation at this time. Such identification may lead to more effective patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate Cancer is the most frequently diagnosed non-skin cancer among men1. The majority of men are diagnosed with early stage disease. In Ireland, 2,400 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer annually with 550 dying each year2. There is no national screening programme for prostate cancer in Ireland. The National Cancer Control Programme developed standards for access to diagnostics and treatment of prostate cancer resulting in 6 Rapid Access Prostate Cancer clinics (RAPC) in the country allowing easier and faster access to specialist urological opinion for men suspected of having prostate cancer3.

Treatments for early stage disease include radical prostatectomy (RP), external beam radiation (EBR), brachytherapy, hormone therapy, a combination of these treatments, active surveillance, or watchful waiting. Each of the active treatments has side effects, the most common of which are urinary, bowel and sexual dysfunction4,5. Due to the high survival rates associated with diagnosis and treatment of early stage disease and studies indicating that many men experience these long term side effects6 it is essential to examine psychological adjustment at each stage of the journey. Added impetus for such research comes from the International Psycho-oncology Society who launched a new standard of Quality Cancer Care proposing that the psychosocial domain be integrated into routine care and that distress be assessed as the sixth vital sign after temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration and pain7. This, together with the recent validation of the Distress Thermometer by Chambers8 will focus attention on emotional indices. This is timely as the majority of research in men with prostate cancer tends to focus on physical and functional issues rather than on immediate emotional experience following diagnosis9,10.

There has been debate on the existence of elevated psychological distress among patients with prostate cancer, with one review reporting no real difference between patients and non patient peers9 and two other reviews reporting elevated levels of anxiety and depression11,12. In a subsequent review Sharpley et al13 concluded that receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer “is highly likely to be a significantly distressing occasion for a substantial proportion of men” (p 571) and in the first meta-analysis of psychological distress in men with prostate cancer, Watts et al.14 reported that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in men with prostate cancer at diagnosis and across the treatment spectrum was relatively high (e.g. pretreatment depression 17.2% and anxiety 27.4%), thus identifying those psychological predictors which explain variability in emotional adjustment is of value.

General perceptions of prostate cancer may predict which individuals have better or worse psychological and physical adjustment during the course of cancer management5. A focus on perceived stress, therefore, may be of greater importance to adaptation than the actual disease stressors themselves15,16. Perceived stress is based on the relationship between the person and the environment and emphasises appraisal of stress. The perception of stress as a threat elicits negative emotional states and maladaptive coping, whereas the perception of stress as a challenge is associated with favourable emotional reactions and greater confidence in coping17. A number of studies have reported significant associations between perceived stress and overall quality of life in mixed cancer groups18 and in men with localised prostate cancer19,20. In the emotional domain, Hsaoi et al.21 found a significant association between global perceived stress and greater prostate cancer symptom distress one to three months post treatment and stress appraisal predicted total mood disturbance in a group of men two years post treatment22. While research in this area is limited, the evidence suggests a link between perceived stress and later psychological adjustment. An exception is a study by Hyacinth et al23 who found no association between these variables in a convenience sample of military personnel.

One of the few studies to date carried out at diagnosis reported that stress appraisal predicted distress a year later24. This concurs with other findings that perceived stress at time of diagnosis is a key predictor of later distress in women with breast cancer16,25. There has been little research on the specific impact of stress appraisals (global or cancer specific) on subsequent health and mood in the prostate cancer population.

Given that cancer in general is an unpredictable illness, its impact on personal mastery beliefs is important26. A number of investigations have examined self-efficacy in relation to patients' adjustment to cancer27,28. Self-efficacy is a broad disposition rooted in the patient's personality and life experience29. It refers to both perception of controllability of self management tasks and sense of efficacy to use skills effectively under difficult circumstances19. Typically in prostate cancer studies, self-efficacy is related to quality of life post-treatment19,30,31. Only two studies to date, have examined the impact of self-efficacy on mood in men with prostate cancer, one demonstrating a link with depression32 and in the other, self-efficacy did not contribute directly to mood disturbance22. Self-efficacy measures used in these studies, however, were, mainly symptom related and men were assessed in the post treatment phase. It would be of value to understand patients' generalised self-efficacy on mood at time of diagnosis before the impact of treatment effects.

Adjustment of men with prostate cancer has usually been assessed in terms of their quality of life, with an emphasis on functional status and physical symptoms. Such measures of quality of life are more relevant during, or post-treatment as at diagnosis many men are asymptomatic. Assessment of mood states, rather than functional adjustment may be more useful at diagnosis.

This study, controlling for age and disease status, examined the role of perceived stress (global and cancer specific) and self-efficacy in predicting emotional adjustment, in men recently diagnosed with localised prostate cancer, who are attending a Rapid Access Prostate Clinic to discuss treatment options.

Methods

Participants

Consecutive men attending the Rapid Access Prostate Clinic, in a university- affiliated hospital over an 8 month period were eligible to participate. The study protocol, which was developed in accordance with the Institutional ethical guidelines for research of the University Hospital, was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were all those newly diagnosed with localised prostate cancer, awaiting treatment, who had completed at least second level education. Exclusion criteria were prior cancer diagnosis or other comorbidities, diagnoses of intellectual disability or psychopathology and lack of literacy skills. An envelope of self report questionnaires including a study stamped addressed envelope was given to them by research assistants (who were health psychology graduates) and the men either filled them in then or returned them within a week. Information on age, medical history and Gleason scores were obtained from hospital records. (Gleason scores consist of 2 numbers, a primary grade and a secondary grade. Each is given a value from 1–5, the higher numbers indicating a more aggressive cancer. The most common score is a 3 + 3 known as Gleason 6)33.

Ethics Statement

We adhere to the guidelines in ‘Use of experimental animals and human subjects’ for articles in Scientific reports. The study protocol adhered to the Institutional ethical guidelines of University Hospital Galway, Ireland and we submitted it for approval to the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital Galway, Ireland. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients at the hospital who participated in the study. We wish to state that this study was conducted with a clinical sample but only group data is provided in the paper. There is no identifying information relating to participants (including patients' details images or videos).

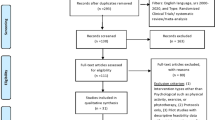

One hundred and five out of 190 patients attending agreed to participate giving a 55% response rate. On checking hospital records, however, 14 of these men satisfied some aspect of the exclusion criteria. Resulting analysis is thus based on 89 eligible men. The non-responders were compared to participants on age and disease status and no differences were found (p's >.05).

Materials

Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)34 includes 10 items (e.g. ‘I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough’) and the responses for each range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The scale provides one overall summative score and has been shown to have high reliability (α = .96). In this study Cronbach's alpha was .89.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)35 taps the degree to which respondents find their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloaded. It is a 14-item scale which refers to events occurring within a one month time frame. Respondents are asked to indicate how often they thought or felt a certain way on a five point Likert scale from 0 “never” to 4 “very often”. Scores can range from 0–56 with higher scores indicating more perceived stress. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was in the acceptable range in the current study (α = .78).

The Impact of Events Scale (IES)36 is a 15-item self report measure of stress related intrusive thoughts, denial of thoughts and avoidant behaviours. It generates a total score based on two subscale scores (intrusion and avoidance). Participants rated each item as experienced in the previous week by using a 4 point Likert scale 0 (not at all), 1 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), 5 (often). Higher scores (0–75) indicate higher levels of cancer related stress. In the present sample, the internal consistency was very good, the coefficient alpha reliability estimate was .92.

The Profile of Moods Scale-Brief (POMS-B)37 is a 30 item indicator of psychological state, used to measure mood disturbance across 6 dimensions: tension/anxiety, depression/dejection, anger/hostility, fatigue/inertia, confusion/bewilderment and vigor/activity. It provides individual subscale scores and a total mood disturbance score. The POMS has been widely used in cancer studies and its psychometric properties are well supported in the literature38. The POMS-B is made up of the 5 highest loading items per subscale based on 6 previous investigations of the POMS37. In this study Cronbach's alpha ranged from .59–.91 for the 6 subscales. The total scale score reliability estimate was .91.

Statistical analyses

A power analysis was conducted using the subject to variable ratio of Tabachnick and Fidell39 and 90 participants were deemed sufficient for a hierarchical multiple regression equation with 5 predictors.

Inspection of histograms and analysis of skewness and kurtosis values for all variables revealed that data were normally distributed. Multicollinearity was assessed among all subscales. Variance Inflation Factor and Tolerance scores for the predictor and outcome variables were acceptable (<10 and >.10 respectively) and can thus be included in a single regression equation. Pearson correlation coefficients assessed relationships between predictors and outcomes.

Hierarchical regression analyses identified sets of variables which significantly predicted adjustment on the 6 indices (tension/anxiety, anger, vigour, fatigue, confusion, depression). The order of entry takes account of self-efficacy beliefs before the impact of stress on adjustment is considered. Steps 1–3 were age and disease status, self-efficacy, stress. Missing data varied from 3% to 9% across the variables. Using Little's MCAR test data was found to be missing completely at random (p > .05) and therefore, the Expectation Maximization algorithm was used to substitute missing values.

Results

The descriptive data are presented in Table 1. The sample scored in the low to moderate range on the stress and mood indices and in the upper range on self-efficacy. The intercorrelations between variables are shown in Table 2 and reveal that relationships between all stress and mood variables are in the expected direction with both high global and cancer specific stress related to high tension, anger, fatigue confusion and depression and high global and cancer specific stress correlated with low vigor. High self-efficacy correlated with good mood across the six scales. The results of the regression analyses are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Variables in step 1 (age and total Gleason score) did not explain a significant amount of variance on any of the mood domains. On step 2, self-efficacy explained variance on six domains; tension (24%), anger (5%), vigor (12%), fatigue (4%), confusion (9%), depression (25%) with beta weights showing relationships in expected directions. The stress set explained additional variance on six domains namely tension (31%), anger (27%), vigor (8%), fatigue (26%), confusion (31%) and depression (29%). In all cases, the beta weights for general stress reached significance showing it was related to poor mood scores. Cancer related stress significantly predicted all mood outcomes, with the exception of vigor. The total amount of variance explained by all predictors for each mood index was as follows; tension (55%), anger (30%), vigor (18%), fatigue, (28%), confusion (40%) and depression (57%).

Discussion

This study focuses on emotional adjustment in men with early localised prostate cancer. A diagnosis of prostate cancer carries a significant emotional burden given the myriad of challenges generating from cancer and its treatment. It is important that health professionals understand men's emotional responses to diagnosis so that they can provide optimal information and psychological care at this time.

In the present study neither disease status or age explained variance on any of the outcomes. This is in line with the finding by Bisson et al.40 that disease status did not predict psychological functioning but contrasts with their finding that younger age was predictive of poor psychological functioning. It is of interest that younger age did not predict mood in the current study given the potential disruptions to family and work life posed by the disease but perhaps in this early phase such disruption had not yet manifested itself. Self-efficacy and stress together explained more than half of the variance on distress (tension and depression) indicating their importance as predictors of mood for this population. Many studies describe levels of emotional distress after diagnosis but rarely focus on psychological predictors of that distress13,41.

Self-efficacy on its own explained variance on all the adjustment indices but particularly on tension and depression with approximately one quarter of the variance being explained on each outcome. This demonstrates the significance of beliefs about personal mastery on adjustment in cancer in line with findings by Pudrovska42. This construct equalled the explanatory impact of stress on distress. The reported relationship in this study between self-efficacy and mood at diagnosis supports the Weber et al.43 finding post treatment while contrasting with a study carried out two years post treatment which found no association between these two variables22. Assessment of this variable at the early phase is of value as it may identify men at risk for poor adaptation at diagnosis. Interestingly, high self-efficacy significantly predicted vigor, (being active and energetic), the only positive emotional index under study. If vigor level can be maintained it may offer resilience for men facing into the treatment phase. Prospective research is needed to ascertain if self-efficacy merits inclusion in psychosocial interventions (enhancing men's ability to manage medical and psychological symptoms). A cancer specific self-efficacy measure administered during treatment would provide important additional data to identify for example, relevant components for an intervention.

In this study the stress set explained variance (ranging from 8%–31%) on all 6 emotional domains, (tension, anger, vigor, fatigue, confusion and depression) with higher levels of reported stress at diagnosis linked to poor emotional adjustment. This concurs with the only other study to examine the relationship between stress and mood using the POMS22, which was at post treatment. Of particular interest, stress best explained confusion/bewilderment emphasising the need for studies to extend beyond the two classic mood states (anxiety and depression) typically included in the cancer literature44,45. It is important to understand factors that modify confusion as at this time men are facing additional responsibility for treatment decisions. Of the two types of stress assessed, perceived global stress emerged as the most powerful predictor for men with prostate cancer. This is in line with previous findings that global stress rather than cancer specific stress predicted adjustment in women with breast cancer16. However, cancer related stress emerged as an equally powerful predictor of tension and explained a greater proportion of variance in confusion than general stress. Thus, measures of intrusion and avoidance may be clinically useful in predicting these particular affective states in men with prostate cancer. It has been reported that avoidance of the threat posed by a cancer diagnosis and treatment is related to poorer, long term adjustment outcomes5. Longitudinal studies are also needed to examine the role of global stress on a wide range of mood domains throughout the prostate cancer trajectory.

A limitation of this study is that it is cross-sectional in nature and so it precludes identification of causal relationships among variables. Prospective studies are thus warranted. Furthermore, the modest sample size and relatively low response rate may influence generalisability of the findings. Socioeconomic status, which could be predictive of mood outcomes, was not measured. The study, however, provides useful insights into possible psychological predictors of men's emotional response to a diagnosis of prostate cancer. It identifies that those high in global and cancer specific stress and low in self-efficacy at diagnosis report poor adjustment and so screening at this early stage may lead to more effective patient management.

References

Vanagas, G., Mickeviciene, A. & Ulys, A. Does quality of life of prostate cancer patients differ by stage and treatment? Scand J Public Healt. 41, 58–64 (2013).

National Cancer Registry, Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 2011: Annual report of the National Cancer Registry (2011); Date of access:16/06/2013. Retrieved from http://www.ncri.ie/pubs.shtml.

Forde, J. C. et al. A rapid access diagnostic clinic for prostate cancer: the experience after one year. Irish J Med Sci. 180, 505–508 (2011).

Eton, D. T. & Lepore, S. J. Prostate cancer and health-related quality of life: A review of the literature. Psychooncology. 11, 307–326 (2002).

Roesch, S. C. et al. Coping with prostate cancer: A meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 28, 281–293 (2005).

Jackson, T. et al. Disclosure of diagnosis and treatment among early stage prostate cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 79, 239–244 (2010).

Watson, M. & Jacobsen, P. Editorial. Stress Health. 28, 353–354 (2012).

Chambers, S. K., Zajdlewicz, L., Youlden, D. R., Holland, J. C. & Dunn, J. The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. PsychoOncology. 23, 195–203 (2013).

Bloch, S. et al. Psychological adjustment of men with prostate cancer: A review of the literature. BioPsychoSoc Med. 1, 1–14 (2007).

Wall, D. P., Kristjanson, L. J., Fisher, C., Boldy, D. & Kendall, G. E. Responding to a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer: Men's experiences of normal distress during the first 3 postdiagnostic months. Cancer Nurs. 36, 44–50 (2013).

Bennett, G. & Badger, T. A. Depression in men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs. 32, 545–556 (2005).

Katz, A. Quality of life for men with prostate cancer. Canc Nurs. 30, 302–308 (2007).

Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V. & Christie, D. H. R. Psychological distress among prostate cancer patients: Fact or fiction? Clin Med Oncol. 2, 563–572 (2008).

Watts, S. et al. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ open. 4, e003901; 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003901 (2014).

Curtis, R., Groarke, A. M., Coughlan, R. & Gsel, A. The influence of disease severity, perceived stress, social support and coping in patients with chronic illness: a 1 year follow up. Psychol Health Med. 9, 456–475 (2004).

Groarke, A. M., Curtis, R. & Kerin, M. Global stress predicts both positive and negative emotional adjustment at diagnosis and post-surgery in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 22, 177–185 (2013).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Personality. 1, 141–169 (1987).

Kreitler, S., Peleg, D. & Ehrenfeld, M. Stress, self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 16, 329–341 (2007).

Lev, E. L. et al. Quality of life of men treated for localized prostate cancer: outcomes at 6 and 12 months. Support Care Cancer. 17, 509–517 (2009).

Love, A. W. et al. Psychosocial adjustment in newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 42, 423–429 (2008).

Hsiao, C. P., Moore, I. M., Insel, K. C. & Merkle, C. J. High perceived stress is linked to afternoon cortisol levels and greater symptom distress in patients with localized prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 36, 470–478 (2011).

Wooten, A. C. et al. Psychological adjustment of survivors of localised prostate cancer: investigating the role of dyadic adjustment, cognitive appraisal and coping style. Psychooncology. 16, 994–1002 (2007).

Hyacinth, L. T. C., Joseph, J., Gregory, L. T. C., Thibault, G. P. & Ruttle-King, J. Perceived stress and quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Mil Med. 171, 425–429 (2006).

Steginga, S. K. & Occhipinti, S. Dispositional optimism as a predictor of men's decision-related distress after localized prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 25, 135–143 (2006).

Golden-Kreutz, D. M. et al. Traumatic stress, perceived glocal stress and life events: prospectively predicting quality of life in breast cancer patients. Health Psychol. 24, 288–296 (2005).

Weber, B. A. et al. The impact of dyadic social support on self-efficacy and depression after radical prostatectomy. J Aging Health. 19, 630–645 (2007).

Porter, L. S., Keefe, F. J., Garst, J., McBride, C. M. & Baucom, D. Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: Associations with symptoms and distress. Pain. 137, 306–315 (2008).

Haas, B. K. Focus on health promotion: self-efficacy in oncology nursing research and practice. Oncol Nurs Forum. 27, 89–97 (2000).

Bandura, A. Self –efficacy: The Exercise of Control. (Freeman, New York, USA, 1997).

Eller, L. S. et al. Prospective study of quality of life of patients receiving treatment for prostate cancer. Nurs Res. 55, 28–36 (2006).

Eton, D. T., Lepore, S. J. & Helgeson, V. S. Early quality of life in patients with localized prostate carcinoma: an examination of treatment-related demographic and psychosocial factors. Cancer. 92, 1451–1459 (2001).

Weber, B. A., Roberts, B. L., Mills, T. L., Chumbler, N. R. & Algood, C. B. Physical and emotional predictors of depression after radical prostatectomy. Am J Mens Health. 2, 165–171 (2008).

Partin, A. W. et al. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer: a multi-institutional update. Jama. 277, 1445–1451 (1997).

Schwarzer, R. & Jerusalem, M. [Generalized self-efficacy scale]. Measures in Health Psychology: A User's Portfolio, Causal and Control Beliefs [Weinman, J., Wright, S. & Johnson, M. (eds)] [35–37] (NFER-NELSON, Windsor, England, 1995).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 24, 385–396 (1983).

Horowitz, M. J., Wilner, N. & Alvarez, W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 41, 209–218 (1979).

McNair, D. M. & Heuchert, J. W. P. Profile of Mood States Technical Update. (MHS, New York, USA, 2003).

Rozsa, S. et al. A study of affective temperaments in Hungary: internal consistency and concurrent validity of the TEMPS-A against the TCI and NEO-PI-R. J Affect Disord. 106, 45–53 (2008).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics (Allyn & Bacon, Boston, USA 2007).

Bisson, J. I. et al. The prevalence and predictors of psychological distress in patients with early localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 90, 56–61 (2002).

Linden, W., Vodermaier, A., MacKenzie, R. & Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender and age. J Affect Disord. 141, 343–351 (2012).

Pudrovska, T. Cancer and mastery: Do age and cohort matter? Soc Sci Med. 71, 1285–1291 (2010).

Weber, B. A. et al. The effect of dyadic intervention on self-efficacy, social support and depression for men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 13, 47–60 (2004).

Okamoto, I., Wright, D. & Foster, C. Impact of cancer on everyday life: A systematic appraisal of the research evidence. Health Expect. 15, 97–111 (2011).

Gil, F., Costa, G., Hilke, I. & Benito, L. First anxiety, afterwards depression: Psychological distress in cancer patients at diagnosis and after medical treatment. Stress Health. 28, 362–367 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by Cancer Care West, Ireland a registered charity (CHY 11260) dedicated to supporting those whose lives have been affected by a cancer diagnosis. The authors wish to acknowledge the excellent collaboration of the medical and nursing staff at the Rapid Access Prostate Clinic at University Hospital, Galway, Ireland. The authors sincerely thank the men for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C and A.M.G. wrote the main manuscript text. F.S. contributed to recruitment and also reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, R., Groarke, A. & Sullivan, F. Stress and self-efficacy predict psychological adjustment at diagnosis of prostate cancer. Sci Rep 4, 5569 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05569

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05569

This article is cited by

-

The association of self-efficacy and health literacy to chemotherapy self-management behaviors and health service utilization

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

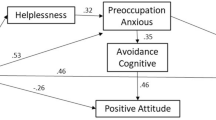

Social support, anxiety, and depression in patients with prostate cancer: complete mediation of self-efficacy

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Introducing two types of psychological resilience with partly unique genetic and environmental sources

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Effect of general self-efficacy on promoting health-related quality of life during recovery from radical prostatectomy: a 1-year prospective study

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2020)

-

Longitudinal course and predictors of communication and affect management self-efficacy among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers

Supportive Care in Cancer (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.