Abstract

Introduction

Vandetanib has recently demonstrated clinically meaningful benefits in patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). Given the potential for long-term vandetanib therapy in this setting, in addition to treatment for disease-related symptoms, effective management of related adverse events (AEs) is vital to ensure patient compliance and maximize clinical benefit with vandetanib therapy.

Methods

This expert meeting-based review aims to summarize published data on AEs associated with vandetanib therapy and to provide clinicians with specific practical guidance on education, monitoring, and management of toxicities induced in patients treated with vandetanib in advanced and metastatic MTC. The content of this review is based on the expert discussions from a multidisciplinary meeting held in October 2012.

Results

Characteristics, frequency, and risk data are outlined for a number of dermatological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and general AEs related to vandetanib treatment. Preventive strategies, practical treatment suggestions, and points for clinical consideration are provided.

Conclusions

Good patient and team communication is necessary for the prevention, early detection, and management of AEs of vandetanib. Physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers play a critical role in providing AE management and patient support to optimize outcomes with vandetanib in MTC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) arises from calcitonin-secreting parafollicular cells of the thyroid and accounts for less than 5% of all thyroid cancers [1]. The 10-year survival rate for patients with MTC is 96% if the disease is treated while the tumor is confined to the thyroid gland [2]. Distant metastases are observed at presentation in 7–23% of patients [1]. Of these, about 40% will die of the disease within 2 years after the diagnosis of distant metastases, whereas about 40% are still alive after 10 years [2]. Altogether, distant metastases are the leading cause of MTC-related death [1].

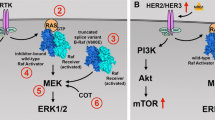

Until recently, therapeutic options for rare cases of advanced, unresectable MTC have been limited, but advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of MTC have led to the development of targeted therapies for this disease. Vandetanib is a once-daily oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that selectively targets the rearranged during transfection (RET) proto-oncogene, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [3, 4]. Vandetanib (Caprelsa®, ZD6474; AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, UK) is the first drug approved for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic disease in the United States and Europe [5, 6]. Long-term treatment with vandetanib has demonstrated a statistically significant longer median progression-free survival versus placebo (30.5 vs 19.3 months; p = 0.001) in this setting [7]. This underscores the need to anticipate and effectively manage therapy-related adverse events (AEs) that will, in turn, promote patient compliance and, therefore, maximize clinical benefit.

Based on clinical studies, the most common AEs reported for vandetanib in MTC are diarrhea, rash and folliculitis, nausea, corrected QT interval (QTc) prolongation, hypertension, and fatigue [7–9]. Endocrine effects evidenced by increased thyroxine, calcium, and vitamin D analog requirements have also been noted [10]. The majority of AEs are manageable according to standard clinical practice alone or in combination with vandetanib dose reductions, and data indicate that severe AEs are not sustained over the course of treatment [11].

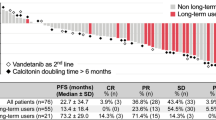

In the Phase III Zactima Efficacy in Thyroid Cancer Assessment (ZETA) study, patients with locally advanced or metastatic MTC were randomized 2:1 to vandetanib 300 mg/day (n = 231) or placebo (n = 100) [7]. Vandetanib treatment led to a significant increase in the primary endpoint of PFS [hazard ratio 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31–0.69, p < 0.001, median follow-up 24 months] versus placebo [7]. The median PFS was 19.3 months in the placebo group, compared with a predicted median PFS of 30.5 months for vandetanib [7]. Vandetanib also demonstrated significantly high rates of objective response (45% versus 13% for placebo; p < 0.001), disease control (87% versus 71%; p = 0.001), and calcitonin biochemical response (69% versus 3%; p < 0.001) [7]. Furthermore, vandetanib was also active in patients with sporadic disease and no detectable RET mutations [7], suggesting that the presence of a RET mutation is not a prerequisite for patients to benefit from treatment [11].

Diarrhea, hypertension, prolongation of the QTc, and fatigue were the most commonly reported (incidence >5%) treatment-emergent grade 3+ AEs in the ZETA trial [7]. Additionally, patients required an increase in thyroid hormone replacement (vandetanib, 49.3% vs placebo, 17.2%). Nearly all patients experienced at least one AE and 55% experienced a grade 3 or higher AE [11]. Most AEs occurred 3–6 months after treatment initiation [11]. Despite the frequency of dose reductions [35% (81/231)] needed with vandetanib, only 12% (28/231) of patients discontinued treatment due to AEs [7].

Rash is the most frequently reported dermatologic AE in vandetanib treatment, occurring in more than 45% of vandetanib-treated patients with MTC in the ZETA trial and is second only to diarrhea [7]. Gastrointestinal (GI) AEs included diarrhea (56%), nausea (33%; 11% grade 3+), decreased appetite (21%), vomiting (14%), and abdominal pain (14%) [7]. Fatigue and asthenia were reported by 24% and 14% of vandetanib-treated patients in ZETA, respectively.

QTc prolongation >500 ms (any grade) was reported by 14% of vandetanib-treated patients in ZETA versus 1% of those receiving placebo [7]. No cases of Torsades de Pointes (TdP) were reported [7], although two patients in a wider drug-safety database had QTc intervals >550 ms (one due to sepsis and one due to heart failure) [6]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis involving patients with a range of tumors (n = 2,188), the overall incidence of all-grade and high-grade QTc interval prolongation with vandetanib 300 mg once-daily was 16.4% (95% CI 8.1–30.4%) and 3.7% (95% CI 1.7–7.8%), respectively, among patients with non-thyroid cancer, and 18.0% (95% CI 10.7–28.6%) and 12.0% (95% CI 4.5–28.0%), respectively, among patients with thyroid cancer [12]. Treatment discontinuations due to QTc prolongation (0.9%) and hypertension (0.9%) have been reported [13].

In this review, we aim to summarize data in the literature on AEs associated with vandetanib therapy and provide community healthcare providers with specific practical guidance on patient education, monitoring, and management of patients taking vandetanib for MTC.

Discussion

The Need for Optimal Management of Vandetanib Therapy in MTC

As the majority of patients who respond to vandetanib are likely to receive this TKI for extended periods of time, all care providers, including community healthcare physicians and nurses, need to have a good understanding of the drug’s safety profile and its potential impact on quality of life and compliance with the drug.

Prior to initiating therapy, a review of past medical history, current comorbidities, and medications should be conducted, with an emphasis on the potential interactions and effects on vandetanib-related AEs. There is controversy in the literature regarding the optimal time to start tumor treatment in patients with advanced MTC [1]. The size and number of tumor foci, and the rate of change of tumor volume during watchful waiting, may help identify the optimal time to commence treatment with vandetanib [6]. The rate of change in serum levels of calcitonin and/or carcinoembryonic antigen may also be taken into account but should not be considered in isolation. Table 1 shows a pragmatic consensus of when to start systemic treatment in patients with advanced MTC.

Vandetanib is typically given initially in MTC as a once-daily 300 mg capsule taken with or without food at about the same time each day [5, 6], which may contribute to patient acceptance and adherence. The prolonged half-life of vandetanib (19 days) is a factor for consideration in the management of any potential AEs [6]; pharmacokinetic data for the drug are published elsewhere [14]. Local prescribing information should be consulted for full details of dosage and administration guidelines for vandetanib therapy.

Dose reduction may result in rapid AE improvement, suggesting a direct toxic effect of the agent. For grade 3 or 4 AEs, vandetanib is discontinued until AEs resolve, after which vandetanib therapy is resumed at a lower dose. Efficacy is observed at doses lower than 300 mg/day [15], and for long-term treatment finding a dose that is well tolerated and allows a normal quality of life may be the best way to ensure patient compliance and avoid self-made adjustments to medication.

Management of Dermatological AEs

Patients who receive vandetanib are at risk of developing a rash (Fig. 1). In a systematic review of trials involving 2,961 patients with a range of tumors, including MTC, the incidence of all-grade and high-grade rash/folliculitis associated with vandetanib 300 mg was 46% (95% CI 40.6–51.8%) and 3.5% (95% CI 2.5–4.7%), respectively [16]. The mechanism of the rash has not been fully elucidated, but most observed rashes, especially those presenting as follicular pustules (Fig. 2), are probably due to the anti-EGFR action of vandetanib, as anti-EGFR agents are associated with acute and subacute folliculitis [17]. It is thought that the ability of vandetanib to block EGFR triggers follicular hyperkeratosis, leading to follicle obstruction and an inflammatory response [18]. There is also a risk of superinfection of these skin lesions.

Other cutaneous AEs observed with vandetanib treatment include photosensitivity, xerosis, finger clefts, paronychia, genital skin reactions, subungual splinter hemorrhages, and blue-gray macules [17]. Photosensitivity is observed in all patients, even through glass behind closed windows, and should be prevented by protection against any sun exposure. Blue-gray macules can be of variable size and are usually located on the face, scalp, or trunk (Fig. 3). They are very similar to the pigmented macules observed on the skin and cornea of patients receiving amiodarone [19], which appear after several months of treatment and usually disappear after treatment interruption. Mucositis, erythrodysesthesia, and hand-foot skin reactions are rare and usually minor [17]. Rarely, serious skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme have been reported [20].

Cosmetically, dermatologic AEs can be debilitating and may adversely affect patients’ quality of life [21], potentially resulting in either interruption or discontinuation of treatment. EGFR inhibitor-related skin toxicity has been associated with a dose reduction in 60% of patients and treatment withdrawal in 32% [22]. Dermatologic AEs led to treatment discontinuation much less frequently in vandetanib-treated patients with MTC than with other treatment options, with rash (1.3%), eczema (0.4%), photosensitivity reactions (0.4%), and pruritus (0.4%) [13].

Although frequent, dermatologic AEs are generally manageable. Before starting vandetanib treatment, it is critical to discuss the potential development of skin reactions with patients, initiate preventive measures, and provide reassurance that these can usually be managed effectively. An evaluation of mucosal and skin surfaces is recommended whenever patients attend clinic. Key management points include strict photoprotection (e.g. use of a broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher, avoidance of any sun exposure by cloth protection) and avoidance of products that dry the skin (e.g. soaps, alcohol-based or perfumed products). Early monitoring is essential to capture the emergence of rash, which is generally treatable. Collaboration with a dermatologist may be needed in severe or complicated cases. Questions to consider when dealing with a rash are listed in Table 2. An extensive review of commonly used topical and systemic therapies to treat skin-related AEs induced by vandetanib is shown in Table 3 [23–26].

Management of Cardiovascular AEs

Increased blood pressure and QTc prolongation have been observed in patients taking vandetanib. Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3,154 patients receiving vandetanib, the incidences of all-grade and high-grade hypertension were 24.2% (95% CI 18.1–30.2%) and 6.4% (95% CI 3.3–9.5%), respectively [27]. Patients with MTC also had a higher incidence of all-grade events than patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and non-MTC/NSCLC tumors receiving vandetanib, with a relative risk of 1.36 (95% CI 1.05–1.76, p = 0.02) and 2.06 (95% CI 1.26–3.36, p = 0.004), respectively, probably due to longer treatment exposure at higher doses [27].

Early detection and effective management of hypertension according to current guidelines is recommended, with close monitoring of blood pressure during the first months of treatment. Pre-existing hypertension should be managed carefully before treatment initiation in line with current guidelines, such as those from the fifth joint task force of the European Society of Cardiology, who define hypertension as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg [28]. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are the most commonly recommended anti-hypertensive drugs for patients under vandetanib treatment. Calcium antagonists and beta-blockers are also helpful if hypertension is not controlled with ACE inhibitors alone. Blood pressure monitoring 1–3 times per month may be done by the patients themselves to allow for close control of hypertension without the need for specific hospital visits.

The AE of most concern with vandetanib is QTc prolongation, particularly in view of the long terminal elimination half-life of the drug [6]. The term “corrected” QT interval may be misunderstood. It relates to the QT interval but is adjusted for heart rate (Fig. 4). Definitions for QTc interval prolongation vary in the literature, and prolongation is characterized either in absolute (e.g. >500 ms) or relative terms (e.g. >30 ms change from baseline in QTc interval). In general, an interval of above 480 ms is considered prolonged.

Schematic representation of normal electrocardiographic trace. The QT interval is a measure of the time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave on an ECG trace. Generally speaking, it represents electrical depolarization and repolarization of the left and right ventricles. A prolonged QT interval is a biomarker for ventricular tachyarrhythmias such as Torsades de Pointes and is a risk factor for sudden death. As the QT interval is influenced by heart rate, the relative risk interval preceding the QT interval is measured to correct for this. ECG electrocardiogram

Accurate measurement of the QTc interval is best performed manually, rather than relying on automatic measurements of standard ECG machines, to guide treatment with QTc-prolonging drugs [29]. Correction formulae such as Bazett’s square root formula (QTc = QT/RR1/2) are frequently used but are often inaccurate at the extremes of physiological heart rate [29]. Use of a QT nomogram, which consists of a plot of QT versus heart rate, is an alternative approach. A QT interval–heart rate pair that plots above an “at-risk” line indicates that the patient is at risk of TdP (Fig. 5) [30].

QTc interval nomogram for determining ‘at risk’ QTc–heart rate pairs from a single 12-lead ECG [30]. Reproduced with permission of The Association of Physicians from Chan et al. [30]. © Oxford University Press. Use: the QTc interval should be measured manually on a 12-lead ECG from the beginning of the Q wave until the end of the T wave in multiple leads (i.e. six leads including limb and chest leads and median QT calculated). The QTc interval is plotted on the nomogram against the heart rate recorded on the ECG. If the point is above the line then the QTc–heart rate is regarded as “at risk”. ECG electrocardiogram, QTc corrected QT

QTc prolongation above 450 ms is associated with a risk of ventricular arrhythmias (e.g. TdP, syncope, and sudden death), and the risk rises with increasing durations of prolongation. First QT prolongations occur most often in the first 3 months of treatment with vandetanib [6].

It is recommended that vandetanib should be withheld if the QTc interval is longer than 500 ms until it returns to 450 ms, upon which a reduced dose can be resumed [5]. A baseline ECG with QTc measurement must be recorded prior to initiation of vandetanib, and vandetanib should not be given to patients with a baseline QTc >450 ms (value may vary depending on local product information). During vandetanib treatment, mean prolongation of QTc is 30 ms. Monitoring of the QTc should be performed at least once every month for the first 3 months on the drug. Vandetanib therapy should be withheld and the patient referred to a cardiologist as soon as any new abnormality following the start of vandetanib treatment is detected. Depending on the clinical situation, close attention to the QTc and even Holter monitoring may be required. Table 4 outlines the principles of managing hypertension and QTc interval prolongation.

The mechanisms of specific cardiovascular AEs in patients with MTC may differ from other tumor types and can limit therapeutic options for other AEs or comorbidities. Factors that may be associated with QTc prolongation include baseline QTc interval, electrolyte levels, and the use of concomitant drugs. It should also be remembered that thyroid function disorders can lead to QTc prolongation and, therefore, need correction [31]. Diarrhea may affect electrolyte balance, necessitating close monitoring of serum potassium, magnesium, and calcium, and this may play a role in the higher incidence of high-grade QTc interval prolongation with vandetanib in thyroid versus other tumor types. Table 5 lists agents that are contraindicated or not recommended for coadministration with vandetanib; an updated list of agents that prolong QTc and/or induce TdP may be found at the Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics (AZERT) CredibleMeds® website [32]. QTc prolongation is rarely a problem when preventive measures are applied, including avoidance of drugs known to prolong the QTc interval, and when hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia are corrected.

Management of Gastrointestinal AEs

Table 6 outlines the recommended treatment and other management considerations for gastrointestinal AEs, which include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Substances used to manage chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting include 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (also known as setrons), dopamine D2 antagonists, and steroids (dexamethasone 8 mg twice daily).

In general, 5-HT3 antagonists are associated with the potential to increase the QTc interval. The use of ondansetron should be avoided in patients being treated with vandetanib, particularly those who have cardiovascular disease and a high risk of drug-induced TdP as well. When used in patients with cardiovascular disease with one or more risk factors for TdP, ondansetron increased the QTc interval by about 19 ms for up to 120 min after administration [33]. Palonosetron represents a new generation of setrons and possesses the highest affinity for the 5-HT3 receptor in this class with the longest half-life of ~40 h [34, 35]. In two small studies of patients receiving chemotherapy, palonosetron did not cause severe rhythmic disorders or symptomatic electrocardiogram (ECG) changes [36], or a statistically significant increase in median QT minimum value [37]. Palonosetron may, therefore, be considered an alternative antiemetic therapy. Nevertheless, caution should be exercised in its concomitant use with medicinal products that increase the QTc interval or in patients who have or are likely to develop prolongation of the QT interval. As palonosetron may increase large bowel transit time, patients with chemotherapy-induced diarrhea could benefit from this substance [34].

The antiemetic action of metoclopramide is based on its D2 receptor antagonist activity. However, at higher doses the substance also exerts 5-HT3 antagonist activity. Thus, metoclopramide may be associated with QTc prolongation and should be used with caution only [38].

Aprepitant is a neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist that is available for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [39]. Signals indicating QT-prolonging properties could not be derived so far from 15 pharmacologic studies [40].

Diarrhea, either due to the disease or treatment, can impair quality of life in patients with MTC, resulting in dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation of therapy. It may also put patients at risk of dehydration with electrolyte disturbance and other potentially life-threatening complications due to the QTc prolongation associated with vandetanib. Diarrhea frequently worsens during antibiotic therapy that may be given for folliculitis.

Diarrhea may also exist in MTC because of the production of hormones that accelerate gastrointestinal motility and may improve with vandetanib treatment. In addition, the use of agents that slow peristaltic movements (e.g. loperamide) or mild opioids (e.g. codeine) can provide relief that is usually partial. Evidence on the efficacy of somatostatin analogs against diarrhea in patients with MTC is not available.

As with other types of AEs, awareness and education regarding GI tolerability is a key part of patient education. Typical measures to take when confronted with diarrhea are listed in Table 2. QTc prolongation can also occur with hypokalemia; therefore, regular monitoring of serum electrolytes is essential. In case of severe GI symptoms, vandetanib should be stopped until symptoms improve. In severe diarrhea persisting after cessations of treatments, a stool work-up should be performed to exclude organic causes.

Management of Generalized AEs

The effect of generalized AEs on quality of life can vary. While many patients are able to maintain normal activity schedules, others experience debilitating fatigue that leads to dose limitation or treatment discontinuation [13]. Fatigue comprises emotional, physical, and/or cognitive tiredness and can be a distressing and persistent AE. It is usually multifactorial and may arise as a symptom of the underlying burden of disease, hypothyroidism, anemia, depression, sleep disturbances, or pain, and can thus be difficult to address. Management of fatigue is primarily supportive; however, it is important to identify treatable causes contributing to it. Patients should be assessed for depression and appropriate treatment measures (avoiding drugs that may prolong QTc) should be introduced to optimize emotional and social support.

Vandetanib treatment in patients with MTC increases visceral fat and muscle body content, in contrast to other TKIs [41]. This positive effect should be taken into consideration and patients on vandetanib should be encouraged to follow a normal social and professional life, and participate in sports activities. It is worth noting that pregnancy constitutes a contraindication for vandetanib therapy and effective contraception is necessary for all patients.

Other AEs reported with vandetanib therapy include reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which requires treatment withdrawal, and cornea verticillata, which is responsible for blue vision and regresses with dose reduction [5].

Nursing Care for Patients Receiving Vandetanib for MTC

As an integral part of a multidisciplinary care team, an experienced specialist nurse is in a unique position to facilitate early detection, intervention, and coordinated management of AEs arising with vandetanib treatment. As a number of AEs are typically seen in the first 3 months of vandetanib treatment, close patient contact is important during this period. Clinic visits may be scheduled every 2 weeks for the first 6–8 weeks to accommodate ECG, serum electrolyte monitoring, and review of emerging AEs.

Apart from providing vital patient education (Table 2), specialist nurses are typically faced with the challenges of eliciting AE information from patients. While some patients may feel more comfortable discussing AEs with a nurse rather than a physician, not all patients realize the importance of reporting specific symptoms and they may not contact the clinic if they experience AEs during treatment. Therefore, it is important that patients are made aware, often by the specialist nurse, of symptoms to look out for and the value of reporting at an early stage. A list of drugs that should be avoided during vandetanib treatment should be given to the patient so that any care provider can check whether a drug can be safely given or not and, in case of doubt, contact a specialist nurse or physician. In addition, patients must be made aware of the importance of informing their specialist nurse and/or physician of any concomitant medication started by other clinicians for comorbidities. These should be carefully documented and cross-checked to avoid possible dangerous drug interactions.

Oncology nurses also have to deal with the logistical impact of geographical distance on patient visits. With the rarity of MTC, it is not unusual for patients to live far away from tertiary care specialist clinics. This may necessitate contact via telephone as a replacement for a clinic visit. If required, a visit from an experienced oncology nurse can be substituted for a doctor’s appointment. Alternative options to ensure open patient communication (e.g. a telephone dedicated by the clinic as a helpline, internet video calls, call center) may be considered, subject to the clinic’s policies and resources. Through effective use of clinical knowledge, patient assessment, and advocacy skills, nurses play a key role in the care of patients with MTC.

Summary and Conclusion

Vandetanib has recently demonstrated clinical benefit in patients with MTC [7]. Other promising agents are in clinical development, and sequencing strategies are likely to expand treatment options and translate to improved survival outcomes in the near future. Patients will potentially receive vandetanib in addition to supportive treatment for comorbidities over a period of several months or years, presenting a unique situation compared with the management of other solid tumor types. With the prospect of longer life expectancy, quality of life is likely to be a determining factor for treatment compliance.

This review proposes pragmatic guidelines for management of AEs related to vandetanib therapy for MTC. For those community physicians who may only treat one or two of these patients per year, we suggest following the “Pocket guidelines for management of vandetanib adverse events” reflected in Table 7.

As with many other targeted cancer therapies, vandetanib is associated with a number of AEs; however, these are generally mild and readily manageable. Informed consent and education about potential treatment-related AEs will help patients anticipate and recognize any tolerability issues with the drug, and active monitoring will allow for early detection and control of AEs that arise. A multidisciplinary approach is strongly recommended, with close coordination and care of patients and their individual needs. These patients have complex requirements and should be treated holistically. The multidisciplinary team, therefore, plays a critical role in providing optimal AE management and patient support to optimize treatment outcomes in this setting.

References

Schlumberger M, Bastholt L, Dralle H, et al. European Thyroid Association guidelines for metastatic medullary thyroid cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2012;1:5–14.

Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer. 2006;107:2134–42.

Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, et al. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284–90.

Wedge SR, Ogilvie DJ, Dukes M, et al. ZD6474 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, angiogenesis, and tumor growth following oral administration. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4645–55.

AstraZeneca 2012. Caprelsa (vandetanib) tablets: US prescribing information. http://www.astrazeneca-us.com/pi/caprelsa.pdf (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2012. Caprelsa (vandetanib): Summary of Product Characteristics, AstraZeneca. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002315/WC500123555.pdf (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

Wells SA Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:134–41.

Wells SA Jr, Gosnell JE, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:767–72.

Leboulleux S, Bastholt L, Krause T, et al. Vandetanib in locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:897–905.

Brassard M, Neraud B, Trabado S, et al. Endocrine effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor vandetanib in patients treated for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2741–9.

Langmuir PB, Yver A. Vandetanib for the treatment of thyroid cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:71–80.

Zang J, Wu S, Tang L, et al. Incidence and risk of QTc interval prolongation among cancer patients treated with vandetanib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30353.

Thornton K, Kim G, Maher VE, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease: U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3722–30.

Martin P, Oliver S, Kennedy SJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of vandetanib: three phase I studies in healthy subjects. Clin Ther. 2012;34:221–37.

Robinson BG, Paz-Ares L, Krebs A, Vasselli J, Haddad R. Vandetanib (100 mg) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2664–71.

Rosen AC, Wu S, Damse A, Sherman E, Lacouture ME. Risk of rash in cancer patients treated with vandetanib: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1125–33.

Giacchero D, Ramacciotti C, Arnault JP, et al. A new spectrum of skin toxic effects associated with the multikinase inhibitor vandetanib. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1418–20.

Peuvrel L, Bachmeyer C, Reguiai Z, et al. Semiology of skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:909–21.

Stahli BE, Schwab S. Amiodarone-induced skin hyperpigmentation. QJM. 2011;104:723–4.

Yoon J, Oh CW, Kim CY. Stevens–Johnson syndrome induced by vandetanib. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:S343–5.

Joshi SS, Ortiz S, Witherspoon JN, et al. Effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced dermatologic toxicities on quality of life. Cancer. 2010;116:3916–23.

Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, Pfeiffer C, Mauro DJ, Lacouture ME. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology. 2007;72:152–9.

Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079–95.

Lynch TJ Jr, Kim ES, Eaby B, Garey J, West DP, Lacouture ME. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: an evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist. 2007;12:610–21.

Lacouture ME, Maitland ML, Segaert S, et al. A proposed EGFR inhibitor dermatologic adverse event-specific grading scale from the MASCC skin toxicity study group. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:509–22.

National Cancer Institute 2010. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40 (Accessed Nov 22, 2012).

Qi WX, Shen Z, Lin F, et al. Incidence and risk of hypertension with vandetanib in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:919–30.

Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): the fifth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Int J Behav Med. 2012;19:403–88.

Isbister GK, Page CB. Drug induced QT prolongation: the measurement and assessment of the QT interval in clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76:48–57.

Chan A, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CM, Dufful SB. Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes: evaluation of a QT nomogram. QJM. 2007;100:609–15.

Fazio S, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, Biondi B. Effects of thyroid hormone on the cardiovascular system. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:31–50.

Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics (AZERT). CredibleMeds(R) website. http://www.crediblemeds.org/everyone/composite-list-all-qtdrugs (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

Hafermann MJ, Namdar R, Seibold GE, Page RL. Effect of intravenous ondansetron on QT interval prolongation in patients with cardiovascular disease and additional risk factors for torsades: a prospective, observational study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2011;3:53–8.

Eisenberg P, MacKintosh FR, Ritch P, Cornett PA, Macciocchi A. Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of palonosetron in patients receiving highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a dose-ranging clinical study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:330–7.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2010. Aloxi (palonosetron) Summary of Product Characteristics, Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals Ltd. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000563/WC500024259.pdf (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

Gonullu G, Demircan S, Demirag MK, Erdem D, Yucel I. Electrocardiographic findings of palonosetron in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1435–9.

Yavas C, Dogan U, Yavas G, Araz M, Ata OY. Acute effect of palonosetron on electrocardiographic parameters in cancer patients: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2343–7.

Rumore MM. Cardiovascular adverse effects of metoclopramide: review of literature. Int J Case Rep Images. 2012;3:1–10.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2008. Emend (aprepitant) Summary of Product Characteristics, Merck Sharp & Dohme. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000527/WC500026537.pdf (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 2003. Aprepitant FDA Advisory Committee Background Package. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/briefing/3928B1_01_Merck%20Backgrounder.pdf (Accessed Sep 10, 2013).

Massicotte MH, Borget I, Broutin S, et al. Body composition variation and impact of low skeletal muscle mass in patients with advanced medullary thyroid carcinoma treated with vandetanib: results from a placebo controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2401–8.

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript is based on the outcomes of a meeting held in October 2012 in Paris, France. The meeting was organized by Enrique Grande and Jaume Capdevila with the assistance of iMed Comms, Macclesfield, UK. Educational funding for the meeting was provided by AstraZeneca through an unrestricted grant. AstraZeneca had no involvement in the organization or content of the meeting.

Caroline Robert, Martin Schlumberger, Lærke K. Tolstrup, and Jaume Capdevila were responsible for developing presentations for the meeting. Jose L. Zamorano reviewed and adapted slides developed by iMed Comms for a presentation on cardiovascular AEs. All authors were present at the meeting and participated actively in the meeting discussions. They have reviewed, commented on, and approved the manuscript outline. All authors reviewed the manuscript drafts critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Medical writing support was provided by Paula Michelle del Rosario, MD, of iMed Comms, Macclesfield, UK, in the form of (1) collation of information on the management of cardiovascular AEs associated with vandetanib, which was requested by Jose L. Zamorano and reviewed by Enrique Grande and Jaume Capdevila; (2) general liaison on presentations prior to the meeting; and (3) development of the manuscript outline under the authors’ direction. iMed Comms also developed the manuscript drafts under direction from the authors. Manuscript development was conducted without input from AstraZeneca. The services provided by iMed Comms were funded by the educational grant provided by AstraZeneca. Funding for the article processing charges and slide deck was provided by AstraZeneca. Enrique Grande is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Enrique Grande received a consulting fee/honorarium from GETHI, support for travel to meetings from GETHI, and a grant from GETHI Group.

Michael C. Kreissl received a consulting fee/honorarium from GETHI, support for travel to meetings from GETHI, and was paid a fee for board membership, consultancy and expert testimony from AstraZeneca and fees for development of educational presentations including speakers’ bureaus from AstraZeneca, Genzyme, and Sanofi Sythelabo.

Sebastiano Filetti received a payment for board membership from NovoNordisk and BMS and fees for development of educational presentations including speakers’ bureaus from AstraZeneca, BMS, Novartis, and NovoNordisk.

Kate Newbold received a consulting fee, honorarium, and support for travel to meetings from GETHI, honoraria for an advisory board, lecture, lecture at the annual Thyroid meeting, and expenses for travel and accommodation for speaking at an ETA meeting from AstraZeneca.

Walter Reinisch received a consulting fee/honorarium and support for travel to meetings from GETHI.

Caroline Robert received a consulting fee from Roche, and a consulting fee/honorarium and support for travel to meetings from GETHI.

Martin Schlumberger received a consulting fee/honorarium and support for travel to meetings from GETHI.

Lærke K. Tolstrup received a consulting fee/honorarium and support for travel to meetings from GETHI.

Jose L. Zamorano received a consulting fee/honorarium from GETHI.

Jaume Capdevila received a consulting fee/honorarium from GETHI.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for which identifying information is included in this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Grande, E., Kreissl, M.C., Filetti, S. et al. Vandetanib in Advanced Medullary Thyroid Cancer: Review of Adverse Event Management Strategies. Adv Ther 30, 945–966 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-013-0069-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-013-0069-5