Abstract

Purpose

As epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors are associated with a variety of dermatologic adverse events (dAEs), the purpose of this study was to develop an overview of current knowledge of dAEs associated with EGFR inhibitors and to identify knowledge gaps regarding incidence, treatment, impact on quality of life (QOL), and patient acceptance.

Method

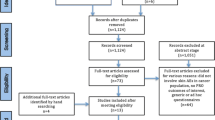

A structured literature search was conducted using MEDLINE/PubMed (January 1983 to January 2014). In total, 71 publications published from 2004 to 2014 were identified for consideration in the final evidence review.

Results

The majority of published articles concentrate on the incidence of skin reactions, duration, treatment, and prevention strategies. Different grading systems based on the symptoms of skin rash or on health-related QOL (HRQOL) are used. An additional topic is the possible correlation between acneiform rash and efficacy of EGFR inhibitors. Knowledge gaps identified in the literature were how dAEs impact QOL compared with other AEs from a patient’s perspective, patients’ acceptance of dAEs (willingness to tolerate), and the impact of physician-patient communication on treatment decisions.

Conclusions

Research is needed on the impact of dAEs on patients’ acceptance of cancer treatments. Systematic studies are missing that compare the impact of dAEs with other toxicities on therapy decisions from both physician’s and patient’s view, and that investigate the balance between efficacy and avoidance of acneiform rash in treatment decisions. Such studies could provide deeper insights into the acceptance of the risk of untoward dermatologic events by both physicians and patients when treating advanced cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, several agents have been developed that inhibit the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which plays a central role in growth of certain cancers. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs; e.g., cetuximab, panitumumab, necitumumab) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; e.g., erlotinib, gefitinib, lapatinib, afatinib) blocking different EGFR targets are therefore an indispensable part of cancer treatment. EGFR inhibitors are used to treat advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (afatinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, necitumumab), pancreatic cancer (erlotinib), breast cancer (lapatinib), colon cancer (cetuximab, panitumumab), and head and neck cancer (cetuximab). Compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy with taxanes, fluoropyrimidines, and platinum compounds that are known to be associated with multiple adverse events (AEs) such as fatigue, pain, nausea and emesis, hematologic toxicity, and neuropathy, EGFR inhibitors may have a lower impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). However, due to the role of EGFR in skin biology, all EGFR inhibitors are associated with a variety of dermatologic AEs (dAEs), e.g., acneiform (papulopustular) rash, hair changes (hair loss, facial hypertrichosis, eyelash trichomegaly), pruritus, mucositis, xerosis and fissures, and paronychia (Fig. 1).

Due to increased incidence of dAEs associated with targeted cancer therapies, a large volume of publications have focused on these toxicities. To get an overview of the current research status and to identify knowledge gaps, this article summarizes the main findings on this topic. It is noteworthy that the severity of patients’ AEs, including those of the skin [1], does not necessarily correlate with the amount to which patients are actually distressed. This requires a special focus on patient-reported outcomes and patients’ HRQOL as part of this literature analysis.

Methods

In the first step, a structured literature search was conducted with the aim of collecting all published articles containing information on ≥1 of the following topics: (1) types of skin toxicities and incidences, (2) toxicity grading systems, (3) prevention and treatment strategies, (4) correlation of rash and efficacy of anti-EGFR therapies, (5) impact of rash on QOL/patient-reported outcomes, and (6) patient acceptance of dAEs/patient adherence.

The literature search was conducted using MEDLINE/PubMed (1st January 1983 to 31st January 2014). MEDLINE contained 17,024,638 articles published during this time period. In addition, further articles were identified by manually searching the references of articles obtained through the electronic search. The search was performed using keywords combined with appropriate operators (AND, OR): (1) skin toxicity (OR skin rash, exanthema, acneiform eruption, dermatology, skin disease) AND (2) EGFR inhibitors (OR anti-EGFR, cancer therapy, monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKIs, cetuximab, Erbitux, panitumumab, Vectibix, erlotinib, Tarceva, gefitinib, Iressa, lapatinib, Tykerb, Tyverb, necitumumab, afatinib, Giotrif, Gilotrif, trametinib, Mekinist, pertuzumab, Jevtana) AND (3) patient acceptance (OR patient-related outcome, patient tolerance, patient reactions, patient compliance, patient adherence, patient persistence, treatment discontinuation, treatment persistence, dose reduction, interrupted treatment, therapy decision, quality of life, QOL, utility assessment, risk-benefit balance). In total, 71 publications (including 10 reviews, guidelines, and recommendations; 60 research studies; and 1 book) published from 2004 to 2014 were identified for consideration in the final evidence review.

Results

Due to the availability of data from clinical studies (interventional as well as non-interventional), the majority of published articles concentrate on the incidence of different dAEs, on treatment and prevention strategies, and on the putative correlation between dAEs and efficacy. Based on the growing knowledge about incidence of skin toxicities, further topics appear in recent publications that are more patient oriented: the impact on QOL and the development of grading systems to assess this impact through patient-reported outcomes and questionnaires. Only a small number of publications refer to patient acceptance of dAEs or to patient adherence to therapies associated with dAEs.

Here, we concentrate on the major findings for each topic, with a more detailed focus on patient-reported outcomes and patients’ HRQOL. Other findings are summarized elsewhere in more detail [2–6].

Incidence of dermatologic adverse events

Skin rash/acneiform rash is the most frequently observed dAE associated with EGFR inhibitors and can be observed in the majority of patients treated with mAbs (Table 1). Other prominent dAEs induced by EGFR inhibitors are xerosis, pruritus, nail changes, mucositis, fissures of fingertips and toes, and hair changes [3–16]. It has been claimed that severe dAEs may result in significant physical and emotional discomfort [15]. However, the incidence of these toxicities alone does not allow drawing conclusions on their impact on QOL. Based on the reported high incidence of dAEs, the authors conclude that dermatologic toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors underscore the importance of dermatologic evaluation, prevention, and treatment of these toxicities [17].

Grading systems for skin rash

Accurate grading of papulopustular rash associated with anti-EGFR therapy is essential to ensure timely and appropriate interventions. Currently, the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) is a widely used classification system in clinical trials. The most recent version (version 4.03) of this tool was published in June 2010 [18, 19]. For example, severe skin rash (grade 3) is defined by papules and/or pustules covering ≥30 % of the body surface area, limited self-care activities of daily living, or associated local superinfection (oral antibiotics indicated). Grade 2 skin rash is described to be “associated with psychosocial impact,” but a validated tool to assess the degree of psychosocial impact is not part of the CTCAE. In addition, the CTCAE scale does not separately characterize the specific dermatologic toxicities observed with EGFR inhibitor therapy (xerosis, pruritus, paronychia, hair abnormalities, and mucositis).

In addition to the CTCAE, several alternative EGFR inhibitor- focused grading systems for dAEs have been proposed in recent years [2, 20–22]. Although several scaling systems exist, no studies have investigated how much these tools are actually used. In particular, it is not known how often current diagnosis of dAEs systematically includes assessment of restrictions in daily and social activities, emotional stress, and the need for dermatologic treatment.

Prevention and treatment strategies

Much of the literature about EGFR inhibitor-induced skin toxicities contains prevention and treatment recommendations [1, 2, 7, 12, 15, 23–29]. Based on the recommendations of the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Skin Toxicity Study Group, clear guidelines for prevention and treatment have been developed, e.g., for skin rash (prevention: hydrocortisone, minocycline; treatment: alclometasone, fluocinonide, clindamycin, doxycycline, minocycline, isotretinoin), radiation-induced dermatitis, pruritus, oral complications, xerosis and fissures, and paronychia. The clinical practice guidelines are summarized in detail elsewhere [15]. However, no studies have investigated how often patients with cancer treated with EGFR inhibitors actually receive a preventive treatment, the criteria used to determine whether patients receive a preventive treatment, and how much dermatologists are involved in treatment recommendations [30].

Correlation of skin rash and efficacy of anti-EGFR therapies

Moreover, numerous studies confirmed that skin rash (the frequently occurring type of dAE caused by EGFR inhibitors) is associated or correlated with efficacy of the EGFR inhibitor therapy [2, 8, 9, 13, 20, 24, 29–52]. Efficacy measures investigated in such studies are usually response rate or overall survival (OS), e.g., by comparing response rates or median OS between subgroups of patients with no rash, grade 1 rash, and grade ≥2 rash. However, the findings do not allow the conclusion that the therapy is not effective if no or only mild dAEs occur. In addition, it is not known whether patients with an advanced stage of cancer actually prefer a cancer therapy with a high risk of severe skin rash even though the therapy does not cure the disease in the majority of cases.

Impact of skin rash on quality of life/patient-reported outcomes

Eleven surveys (2007–2013) that report results on the impact of skin rash on HRQOL were identified and analyzed. Ten surveys report a negative impact on HRQOL, particularly with higher grades of skin rash (grade ≥2) [38, 53–61]. Only one author reports no correlation of grade of skin toxicity with QOL regarding the difference in QOL between patients with skin rash grade 0/1 vs grade ≥2 [47]. However, this study used the EQ-5D to assess QOL, and the EQ-5D is a general QOL measure that is not tailored to measure QOL related to skin conditions.

To assess HRQOL, different tools are available as follows: Skindex-16 [38, 62], Skindex-29 [62], Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)-EGFRI-18 [54], DIELH [60], Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [56, 63], and general assessments of QOL through HRQL [64] or EQ-5D [47].

The two Skindex questionnaires (1 with 16 items, 1 with 29 items) measure comprehensively the effects of skin disease on different dimensions of HRQOL: symptoms (e.g., itching, burning sensations), emotions (e.g., frustration, embarrassment, feeling depressed), and functions (e.g., effect on relationships, daily activities, and work). Skindex-16 is a brief version (one-page questionnaire) assessing not only how often patients have a particular experience but also how much they are bothered by it. Each question asks the patient to quantify how much a specific aspect of his or her skin condition bothered him or her in the week prior to administration of the questionnaire. The overall score can be further divided into three subscales: the patient’s emotional state, symptom severity, and functioning state. All published studies using Skindex reported a lower QOL for patients with papulopustular rash. The correlation is based on the concordance between QOL score and graded severity using CTCAE: the higher the graded severity of rash, the lower the reported QOL. The impact is highest on the emotional dimension [38]. Furthermore, QOL is affected more in younger patients aged <50 years. Targeted therapies associated with dAEs are also more often associated with a lower QOL than non-targeted therapies [58], again with strongest expression in the emotions domain.

Studies using scales other than Skindex to measure HRQOL support the hypothesis of the negative impact of dAEs on QOL as well, but with smaller sample sizes. For example, one study using DLQI [56] identified 4 out of 16 patients with skin rash grade ≥2, and all reported a moderate to strong impact on QOL. Finally, FACT-EGFR-18 is a validated instrument with18 items, including subscales for physical well-being (e.g., “My skin or scalp itches”), social/emotional well-being (e.g., “My skin condition affects my mood”; “I avoid going out in public because of how my skin looks”), and functional well-being (e.g., “My skin condition interferes with my ability to sleep”) [54]. A small sample with 10 patients treated with EGFR inhibitors showed significant correlations between intensity of dAEs and QOL.

Although the results clearly support the assumption that the QOL of patients with cancer is affected by the occurrence of dAEs induced by EGFR inhibitors (in particular, skin rash grade ≥2), the sample sizes in the current literature are rather small, and the use of these tools is currently not part of standard clinical practice. The results mainly provide insights on how the emotional and social dimensions of life are affected by physical conditions, but no conclusions can be drawn regarding whether patients and/or physicians are less motivated to use cancer therapies causing both (severe) dAEs and worsened psychosocial well-being.

Patient acceptance of skin toxicities/patient adherence

Only a few publications report on patient acceptance of dAEs caused by EGFR therapies [5, 56, 65–69]. Most of the studies provide data about the frequency of dose reductions or therapy terminations due to skin toxicities. The rate of dose reductions or treatment terminations can be interpreted as an indicator of low patient adherence and probably also as an indicator of low patient acceptance. In five surveys on erlotinib, dose reductions in 11 to 17 % of patients were necessary due to skin toxicities; 4 to 14 % of patients terminated the treatment (Table 2).

Across all studies, treatment was interrupted by the patients mainly because of grade ≥3 toxicities, but there are no published data clarifying whether the decision was made by the patients or the physicians. In a large study including 427 patients treated with erlotinib [67], 12 % of patients required dose reductions to 100 mg daily because of drug-related rash, and 14 % required treatment interruptions because of rash. Nine percent of the total erlotinib group had grade ≥3 rash. According to this study, treatment modification was not recommended for grade 1 or 2 rash [67]. For grade 3 rash, treatment was withheld, the rash was treated symptomatically, and erlotinib was restarted at a dose of 100 mg daily when the rash was grade ≤1.

Only one study assessed patient concerns about dAEs during treatment irrespective of dose modifications or terminations [56]. In this retrospective survey, 16 patients treated with EGFR inhibitors were asked whether, at some time during the treatment, they had wanted to stop treatment for dermatologic reasons. Three patients answered positively. Two of them had experienced grade ≥3 dAEs, justifying treatment discontinuation according to the clinical grade. One patient, however, wanted to stop EGFR inhibitors because of the severe psychological impact of facial skin and hair modifications despite moderate clinical grading of these changes. None of the 13 remaining patients wanted to stop therapy because of cutaneous toxicities, including four patients with grade 3 dAEs who stopped treatment following medical advice because of severe dAEs. In total, in 6 of the 16 patients (37 %), EGFR inhibitors had been temporarily discontinued: three patients on cetuximab (grade 3 folliculitis), two patients on erlotinib (one with grade 3 folliculitis, one with atypical rash and paronychia), and one on panitumumab (painful digital fissures). Although the survey included a rather small number of patients (n = 16), the results showed that some patients considered stopping therapy even though they did not actually stop, and some patients did not consider stopping therapy even though they did stop on the advice of healthcare professionals.

Considering the few studies addressing low patient adherence, it is clear that patient acceptance of skin toxicities is only indirectly addressed by studies investigating dose modifications or treatment discontinuations due to AEs. High-grade skin toxicity leads to treatment interruption and dose reduction. Data on dose adjustments are usually assessed as a part of clinical trials (not as primary endpoints), but the incidence of dose adjustments cannot be equated with low patient acceptance of AEs because more patients may be psychologically distressed than indicated by the number whose dose was changed or who terminated treatment.

Discussion

This literature survey clearly demonstrates that there is abundant information about the incidence of dAEs caused by EGFR inhibitors (>70 % all grades; 9–10 % grade 3; higher incidence in mABs than in TKIs). Accordingly, prevention and treatment of skin toxicities is an important topic in clinical practice, at least at the level of treatment guidelines. Based on correlation studies, the occurrence and the severity of dAEs are associated with higher response rates and a survival benefit, but dAEs are also associated with lower HRQOL, particularly for severe skin rash. Several tools are available that can be used to measure HRQOL in patients treated with EGFR inhibitors, but it is unclear to what extent these tools are actually used. The incidence of dose reductions and treatment terminations due to dAEs (mainly skin rash) support the hypothesis that the dAEs that occur exceed a threshold of acceptance. However, the data are often unplanned by-products of larger clinical trials that are focused on response rates, progression-free survival, or OS as primary endpoints.

Of 70 publications on skin toxicities associated with the use of EGFR inhibitors, there is only one study (with only 16 patients) that directly addresses patient concerns about dAEs during treatment [56]. The available tools used for grading dAEs and assessing their impact on QOL refer mainly to the severity of reported dAEs and their impact on emotional, social, or functional aspects of QOL. However, they do not reflect how patients actually think about dAEs, how patients evaluate these events compared with other AEs caused by cancer therapies, and to what extent these events are accepted in relation to the efficacy of cancer therapies. In addition, the available data do not provide any insights on the physician-patient interaction before, during, or after drug treatment. In clinical practice, balancing different benefits and disadvantages of treatment options occurs every day when treatment decisions are made, and the opinions of both healthcare practitioners and patients need to be considered. Therefore, we conclude that the next generation of research projects on dAEs caused by cancer therapies should address missing information regarding the following issues: (1) lack of patient voice, (2) physician-patient communication regarding dAEs, (3) acceptance of (severe) skin toxicities compared with other AEs, and (4) balancing the risk of (severe) skin toxicities and the efficacy of the therapy.

(1) Overcome the issue of the missing patient voice

To better understand patients’ beliefs regarding dAEs, future studies on dAEs should assess the experiences and opinions of patients with cancer regarding the occurrence of skin rash or other skin toxicities during treatment. For this purpose, FACT-EGFRI-18 was developed to assess dermatologic symptoms associated with EGFR inhibitors. In addition, gathering information through patient interviews is useful, either retrospectively after treatment or during treatment with EGFR inhibitors. What are patients’ first reactions when dAEs occur, and to what extent are patients prepared by physicians for the occurrence of dAEs? Which aspects of dAEs are most bothersome (e.g., itching, dry skin, skin rash on the face vs other regions, duration of skin rash)? Do patients accept these AEs as part of the cancer treatment? What has been done to prevent or treat dAEs in patients treated with EGFR inhibitors? Which activities of daily living are affected? The main benefit of gathering this information is to find leverage points for prevention and patient education, similar to patient education on other AEs, such as alopecia, anemia, and neutropenia [7, 9, 21, 22, 31, 35, 61, 64, 70, 71].

(2) Gather information on physician-patient communication regarding dAEs

Communication about skin toxicities like skin rash includes various aspects: informing the patient about dAEs before starting the therapy (or during therapy decision), deciding about preventive measures, using patient brochures (Supplemental Figure 1), communicating with the patient when dAEs occur, and deciding about treatment of dAEs (which includes referrals to dermatologists). In the current publications, none of these aspects of physician-patient communication were investigated. For example, in the phase of patient education before starting the therapy, it is currently unknown how many patients treated with EGFR inhibitors are informed about the risk of dAEs. In addition, published data do not contain any information on how physicians explain dAEs (for example, skin rash) to their patients: using words like “rash,” “acne,” or “pustules” may lead to a patient’s incorrect understanding of this type of AEs. To what extent are patients shown pictures to demonstrate what a skin rash looks like? What else is said to the patient regarding dAEs, e.g., about itching and inflammation of skin areas and whether this is an indicator of efficacy or at least that the agent is active? One goal of future research will be to describe in detail what physicians tell their patients and what sticks in the minds of the patients. Based on the results of such surveys, it would be easier to make the current communication more effective by emphasizing certain aspects of skin rash that are currently not well understood by patients [42, 55, 72].

(3) Provide insights into acceptance of (severe) skin toxicities compared with other AEs

Because studies have focused on dAEs, the impact of these events on QOL compared with that of other AEs has been insufficiently investigated. The same concern applies to patient acceptance of dAEs compared with other AEs. Such information could be quite easily gathered, for example, through paired-comparison methodologies, with the patient asked to select the most bothersome AE from two options, or to select one therapy among several treatment options that differ only regarding their AEs (e.g., severe skin rash vs hair loss vs fatigue/tiredness vs nausea/vomiting). To get valid results, it will be important to conduct such a survey with patients with cancer who have been treated with EGFR inhibitors and who already experienced dAEs. Conducting the same exercise with treating physicians would provide insights about differences between physicians’ and patients’ perception of the burden of AEs. For example, physicians observing dAEs with different grades among many patients might overestimate the bothersome impact of dAEs compared with patients.

(4) Collect information on balancing the risk of (severe) skin toxicities and the efficacy of the therapy

Treatment decisions are not made simply by selecting one therapy with the least bothersome AE. In clinical practice, the decision process is influenced by multiple factors, for example, tumor histology, tumor stage, rate of progression, patient’s performance status, patient features (e.g., age, sex, smoking status), cancer therapies used in earlier treatment lines, clinical trial results of treatment options, structure of the patient samples in clinical trials, availability of anticancer drugs, and personal experience with the available drugs. Once a list of the most suitable treatment options for an individual patient is determined, one option is selected based on the balance between acceptable AEs and expected efficacy. For example, a patient with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer could be treated in the first line with an EGFR inhibitor (one of the available TKIs) or with chemotherapy. The TKI is associated with a certain risk of skin rash or other AEs (e.g., diarrhea). As the currently approved TKIs are efficacious regarding the chance of controlling the tumor or prolonging life for a certain number of months, the decision seems to be easy. Not accepting the risk of severe skin rash (occurring in about 9 % of the patients treated with oral TKIs) would mean that the patient and the treating team of physicians would forgo the chance of controlling the tumor. Because many patients with advanced lung cancer are treated with TKIs (particularly when their disease is EGFR-mutation positive), the decision between avoiding skin rash and accepting it (with the chance of controlling the disease for a certain amount of time) is obviously toward skin rash acceptance; otherwise, patients would not be treated with EGFR inhibitors. The psychological reasons for this decision are probably the fact that skin rash is not life-threatening (no case of grade 5 skin rash has been reported), the symptoms are transitional (maximum intensity after 2 to 3 weeks, total duration until crusting of eruptions and the phase of dry skin 5 to 8 weeks [6, 21, 72, 73]), physicians do not describe grade 3 severe skin rash in detail, or less informed patients associate it with juvenile acne. However, so far, no study has been conducted that systematically investigates the balance between seeking efficacy and avoiding severe skin rash risk. What probability of severe skin rash is accepted at a given level of efficacy? And how to balance tumor control with a given probability of severe skin rash? Such studies should involve both physicians and patients with an advanced stage of tumor development in order to compare both groups.

Conclusion

More research is needed on the impact of dAEs on patients’ acceptance of cancer treatments. Although reduced HRQOL, dose modifications, and therapy discontinuations have been reported in patients with severe skin toxicity, systematic studies are missing that compare the impact of dAEs with the impact of other toxicities on therapy decisions from both the physician’s and patient’s view.

To overcome the issue of the rare patient voice, the next generation of patient-related outcome studies should provide deeper insights into how the risk of (severe) skin rash is accepted by both physicians and patients, and how efficacious a cancer therapy should be at a given risk of severe skin rash. Such insights might especially highlight the balance between AEs and efficacy that needs to be achieved for a cancer drug to be perceived as valuable by patients and physicians.

References

Basch E (2010) The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med 362:865–869

Alberta Health Services (2012) Prevention and treatment of rash in patients treated with EGFR inhibitor therapies. Clinical Practice Guidelines SUPP-003, v1. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-supp003-egfri-rash.pdf. Accessed 12/15 2016

Balagula Y, Lacouture ME, Cotliar JA (2010) Dermatologic toxicities of targeted anticancer therapies. J Support Oncol 8:149–161

Tan EH, Chan A (2009) Evidence-based treatment options for the management of skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 43:1658–1666

Lacouture ME (2014) Dermatologic Principles and Practice in Oncology: Conditions of the Skin, Hair and Nails in Cancer Patients. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken

Potthoff K, Hofheinz R, Hassel JC, Volkenandt M, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, Karthaus M, Riess H, Lipp HP, Hauschild A, Trarbach T, Wollenberg A (2011) Interdisciplinary management of EGFR-inhibitor-induced skin reactions: a German expert opinion. Ann Oncol 22:524–535

Burish TG, Snyder SL, Jenkins RA (1991) Preparing patients for cancer chemotherapy: effect of coping preparation and relaxation interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:518–525

Ensslin CJ, Rosen AC, Wu S, Lacouture ME (2013) Pruritus in patients treated with targeted cancer therapies: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 69:708–720

Frith H, Harcourt D, Fussell A (2007) Anticipating an altered appearance: women undergoing chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11:385–391

Krueger C (2010) Management of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor-Induced Dermatologic Toxicity

Lacouture ME, Schadendorf D, Chu CY, Uttenreuther-Fischer M, Stammberger U, O’Brien D, Hauschild A (2013) Dermatologic adverse events associated with afatinib: an oral ErbB family blocker. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 13:721–728

Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, Xu F, Yassine M (2010) Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-emptive skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1351–1357

Rowinsky EK, Schwartz GH, Gollob JA, Thompson JA, Vogelzang NJ, Figlin R, Bukowski R, Haas N, Lockbaum P, Li YP, Arends R, Foon KA, Schwab G, Dutcher J (2004) Safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity of ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 22:3003–3015

Segaert S, Van Cutsem E (2005) Clinical signs, pathophysiology and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Oncol 16:1425–1433

Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, Bryce J, Chan A, Epstein JB, Eaby-Sandy B, Murphy BA, MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group (2011) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer 19:1079–1095

Chan A, Cameron MC, Garden B, Boers-Doets CB, Schindler K, Epstein JB, Choi J, Beamer L, Roeland E, Russi EG, Bensadoun RJ, Teo YL, Chan RJ, Shih V, Bryce J, Raber-Durlacher J, Gerber PA, Freytes CO, Rapoport B, LeBoeuf N, Sibaud V, Lacouture ME (2015) A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of dermatologic adverse events associated with targeted cancer therapies. Support Care Cancer 23:2231–2244

Jia Y, Lacouture ME, Su X, Wu S (2009) Risk of skin rash associated with erlotinib in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Support Oncol 7:211–217

Chen AP, Setser A, Anadkat MJ, Cotliar J, Olsen EA, Garden BC, Lacouture ME (2012) Grading dermatologic adverse events of cancer treatments: the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0. J Am Acad Dermatol 67:1025–1039

National Cancer Institute (2010) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 4.03. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2015

Abdullah SE, Haigentz M Jr, Piperdi B (2012) Dermatologic toxicities from monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR: pathophysiology and management. Chemother Res Pract 2012:351210

McGarvey EL, Baum LD, Pinkerton RC, Rogers LM (2001) Psychological sequelae and alopecia among women with cancer. Cancer Pract 9:283–289

Williams SA, Schreier AM (2004) The effect of education in managing side effects in women receiving chemotherapy for treatment of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 31:E16–E23

Grenader T, Gipps M, Goldberg A (2008) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia secondary to severe erlotinib skin toxicity. Clin Lung Cancer 9:59–60

Hecht JR, Patnaik A, Berlin J, Venook A, Malik I, Tchekmedyian S, Navale L, Amado RG, Meropol NJ (2007) Panitumumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 110:980–988

Jatoi A, Green EM, Rowland KM Jr, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR (2009) Clinical predictors of severe cetuximab-induced rash: observations from 933 patients enrolled in North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study N0147. Oncology 77:120–123

Jatoi A, Dakhil SR, Sloan JA, Kugler JW, Rowland KM Jr, Schaefer PL, Novotny PJ, Wender DB, Gross HM, Loprinzi CL, North Central Cancer Treatment Group (2011) Prophylactic tetracycline does not diminish the severity of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor-induced rash: results from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (Supplementary N03CB). Support Care Cancer 19:1601–1607

Jatoi A, Thrower A, Sloan JA, Flynn PJ, Wentworth-Hartung NL, Dakhil SR, Mattar BI, Nikcevich DA, Novotny P, Sekulic A, Loprinzi CL (2010) Does sunscreen prevent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor-induced rash? Results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N05C4). Oncologist 15:1016–1022

Li J, Peccerillo J, Kaley K, Saif MW (2009) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia related with erlotinib skin toxicity in a patient with pancreatic cancer. JOP 10:338–340

Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJS, Needle MN, Kopit J, Mayer RJ (2004) Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol 22:1201–1208

Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, Pfeiffer C, Mauro DJ, Lacouture ME (2007) Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology 72:152–159

Dudek AZ, Kmak KL, Koopmeiners J, Keshtgarpour M (2006) Skin rash and bronchoalveolar histology correlates with clinical benefit in patients treated with gefitinib as a therapy for previously treated advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 51:89–96

Azim HA Jr, Agbor-Tarh D, Bradbury I, Dinh P, Baselga J, Di Cosimo S, Greger JG Jr, Smith I, Jackisch C, Kim SB, Aktas B, Huang CS, Vuylsteke P, Hsieh RK, Dreosti L, Eidtmann H, Piccart M, de Azambuja E (2013) Pattern of rash, diarrhea, and hepatic toxicities secondary to lapatinib and their association with age and response to neoadjuvant therapy: analysis from the NeoALTTO trial. J Clin Oncol 31:4504–4511

Baselga J, Trigo JM, Bourhis J, Tortochaux J, Cortes-Funes H, Hitt R, Gascon P, Amellal N, Harstrick A, Eckardt A (2005) Phase II multicenter study of the antiepidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody cetuximab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with platinum-refractory metastatic and/or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 23:5568–5577

Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Cohen RB, Jones CU, Sur RK, Raben D, Baselga J, Spencer SA, Zhu J, Youssoufian H, Rowinsky EK, Ang KK (2010) Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol 11:21–28

Colagiuri B, Dhillon H, Butow PN, Jansen J, Cox K, Jacquet J (2013) Does assessing patients’ expectancies about chemotherapy side effects influence their occurrence? J Pain Symptom Manage 46:275–281

Faehling M, Eckert R, Kuom S, Kamp T, Stoiber KM, Schumann C (2010) Benefit of erlotinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer is related to smoking status, gender, skin rash and radiological response but not to histology and treatment line. Oncology 78:249–258

Johnson JR, Cohen M, Sridhara R, Chen YF, Williams GM, Duan J, Gobburu J, Booth B, Benson K, Leighton J, Hsieh LS, Chidambaram N, Zimmerman P, Pazdur R (2005) Approval summary for erlotinib for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen. Clin Cancer Res 11:6414–6421

Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Au HJ, Berry SR, Krahn M, Price T, Simes RJ, Tebbutt NC, van Hazel G, Wierzbicki R, Langer C, Moore MJ (2007) Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 357:2040–2048

Leporini C, Saullo F, Filippelli G, Sorrentino A, Lucia M, Perri G, Gattuta GL, Infusino S, Toscano R, Dima G, Olivito V, Paletta L, Bottoni U, De Sarro G (2013) Management of dermatologic toxicities associated with monoclonal antibody epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a case review. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 4:S78–S85

Mita AC, Papadopoulos K, de Jonge MJ, Schwartz G, Verweij J, Mita MM, Ricart A, Chu QS, Tolcher AW, Wood L, McCarthy S, Hamilton M, Iwata K, Wacker B, Witt K, Rowinsky EK (2011) Erlotinib ‘dosing-to-rash’: a phase II intrapatient dose escalation and pharmacologic study of erlotinib in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 105:938–944

Mohamed MK, Ramalingam S, Lin Y, Gooding W, Belani CP (2005) Skin rash and good performance status predict improved survival with gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 16:780–785

Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Aziz NM, Blanch-Hartigan D, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Weaver KE (2014) Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 32:4087–4094

Perez-Soler R, Chachoua A, Hammond LA, Rowinsky EK, Huberman M, Karp D, Rigas J, Clark GM, Santabarbara P, Bonomi P (2004) Determinants of tumor response and survival with erlotinib in patients with non--small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 22:3238–3247

Pircher A, Ulsperger E, Hack R, Jamnig H, Pall G, Zelger B, Sterlacci W, Hilbe W, Fiegl M (2011) Basic clinical parameters predict gefitinib efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 31:2949–2955

Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarwala SS, Siu LL (2004) Multicenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 22:77–85

Sugiura Y, Nemoto E, Kawai O, Ohkubo Y, Fusegawa H, Kaseda S (2013) Skin rash by gefitinib is a sign of favorable outcomes for patients of advanced lung adenocarcinoma in Japanese patients. Springerplus 2:22-1801-2-22. Epub 2013 Jan 23

Thaler J, Karthaus M, Mineur L, Greil R, Letocha H, Hofheinz R, Fernebro E, Gamelin E, Banos A, Kohne CH (2012) Skin toxicity and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer during first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI treatment in a single-arm phase II study. BMC Cancer 12:438-2407-12-438

Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, Humblet Y, Hendlisz A, Neyns B, Canon JL, Van Laethem JL, Maurel J, Richardson G, Wolf M, Amado RG (2007) Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:1658–1664

Van Cutsem E, Tejpar S, Vanbeckevoort D, Peeters M, Humblet Y, Gelderblom H, Vermorken JB, Viret F, Glimelius B, Gallerani E, Hendlisz A, Cats A, Moehler M, Sagaert X, Vlassak S, Schlichting M, Ciardiello F (2012) Intrapatient cetuximab dose escalation in metastatic colorectal cancer according to the grade of early skin reactions: the randomized EVEREST study. J Clin Oncol 30:2861–2868

Vincenzi B, Santini D, Rabitti C, Coppola R, Beomonte Zobel B, Trodella L, Tonini G (2006) Cetuximab and irinotecan as third-line therapy in advanced colorectal cancer patients: a single centre phase II trial. Br J Cancer 94:792–797

Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, Witt K, Clark G, Cagnoni PJ (2007) Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res 13:3913–3921

West HL, Franklin WA, McCoy J, Gumerlock PH, Vance R, Lau DH, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, Gandara DR (2006) Gefitinib therapy in advanced bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group Study S0126. J Clin Oncol 24:1807–1813

Andreis F, Rizzi A, Mosconi P, Braun C, Rota L, Meriggi F, Mazzocchi M, Zaniboni A (2010) Quality of life in colon cancer patients with skin side effects: preliminary results from a monocentric cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8:40-7525-8-40

Boers-Doets CB, Gelderblom H, Lacouture ME, Bredle JM, Epstein JB, Schrama NA, Gall H, Ouwerkerk J, Brakenhoff JA, Nortier JW, Kaptein AA (2013) Translation and linguistic validation of the FACT-EGFRI-18 quality of life instrument from English into Dutch. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17:802–807

Munhoz BA, Paiva HS, Abdalla BM, Zaremba G, Rodrigues AM, Carretti MR, Monteiro CR, Zara A, Silva JO, Assis WB, Auresco LC, Pereira LL, Giglio AB, Lepori AC, Trufelli DC, del Giglio A (2014) From one side to the other: what is essential? Perception of oncology patients and their caregivers in the beginning of oncology treatment and in palliative care. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 12:485–491

Osio A, Mateus C, Soria JC, Massard C, Malka D, Boige V, Besse B, Robert C (2009) Cutaneous side-effects in patients on long-term treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Br J Dermatol 161:515–521

Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, Tulipani C, Mattioli V, Colucci G (2010) Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 18:329–334

Rosen AC, Case EC, Dusza SW, Balagula Y, Gordon J, West DP, Lacouture ME (2013) Impact of dermatologic adverse events on quality of life in 283 cancer patients: a questionnaire study in a dermatology referral clinic. Am J Clin Dermatol 14:327–333

Sibaud V, Dalenc F, Chevreau C, Roche H, Delord JP, Mourey L, Lacaze JL, Rahhali N, Taieb C (2011) HFS-14, a specific quality of life scale developed for patients suffering from hand-foot syndrome. Oncologist 16:1469–1478

Unger K, Niehammer U, Hahn A, Goerdt S, Schumann M, Thum S, Schepp W (2013) Treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with cetuximab: influence on the quality of life. Z Gastroenterol 51:733–739

Wagner LI, Berg SR, Gandhi M, Hlubocky FJ, Webster K, Aneja M, Cella D, Lacouture ME (2013) The development of a Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) questionnaire to assess dermatologic symptoms associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (FACT-EGFRI-18). Support Care Cancer 21:1033–1041

Chren MM (2012) The Skindex instruments to measure the effects of skin disease on quality of life. Dermatol Clin 30:231–6, xiii

Department of Dermatology, Cardiff University School of Medicine. Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI). http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/files/2014/07/DLQI.pdf. Accessed December 15 2015

Wagner LI, Lacouture ME (2007) Dermatologic toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors: the clinical psychologist’s perspective. Impact on health-related quality of life and implications for clinical management of psychological sequelae. Oncology (Williston Park) 21:34–36

Binder D, Buckendahl AC, Hubner RH, Schlattmann P, Temmesfeld-Wollbruck B, Beinert T, Suttorp N (2012) Erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: impact of dose reductions and a novel surrogate marker. Med Oncol 29:193–198

Reck M, van Zandwijk N, Gridelli C, Baliko Z, Rischin D, Allan S, Krzakowski M, Heigener D (2010) Erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: efficacy and safety findings of the global phase IV Tarceva Lung Cancer Survival Treatment study. J Thorac Oncol 5:1616–1622

Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, van Kooten M, Dediu M, Findlay B, Tu D, Johnston D, Bezjak A, Clark G, Santabarbara P, Seymour L, National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (2005) Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 353:123–132

Tiseo M, Gridelli C, Cascinu S, Crino L, Piantedosi FV, Grossi F, Brandes AA, Labianca R, Siena S, Amoroso D, Belvedere O, Valentino B, Bearz A, Venturino P, Ardizzoni A (2009) An expanded access program of erlotinib (Tarceva) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): data report from Italy. Lung Cancer 64:199–206

Yeo WL, Riely GJ, Yeap BY, Lau MW, Warner JL, Bodio K, Huberman MS, Kris MG, Tenen DG, Pao W, Kobayashi S, Costa DB (2010) Erlotinib at a dose of 25 mg daily for non-small cell lung cancers with EGFR mutations. J Thorac Oncol 5:1048–1053

Borsellino M, Young MM (2011) Anticipatory coping: taking control of hair loss. Clin J Oncol Nurs 15:311–315

Waters EA, Weinstein ND, Colditz GA, Emmons K (2009) Explanations for side effect aversion in preventive medical treatment decisions. Health Psychol 28:201–209

Girones R (2015) Desire for information in the elderly: interactions with patients, family, and physicians. J Cancer Educ 30:766–773

Lacouture ME (2006) Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer 6:803–812

Kuenen B, Witteveen PO, Ruijter R, Giaccone G, Dontabhaktuni A, Fox F, Katz T, Youssoufian H, Zhu J, Rowinsky EK, Voest EE (2010) A phase I pharmacologic study of necitumumab (IMC-11F8), a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against EGFR in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 16:1915–1923

Acknowledgments

Copy editing assistance was provided by ClinicalThinking, Inc, and funded by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. This research was funded in part through the NIH/Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Contributors

BT: had the initial idea for this study and outlined the content and structure of the literature research.

RH: performed the literature research and analyzed relevant sources.

MK: continuously monitored the analysis regarding structure, topics, and results.

ML: consulted the research team regarding all medical questions.

BT: wrote the first draft. RH, MK, and ML commented on and contributed to the final draft.

The authors take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Funding

This literature survey was supported by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Conflict of interest

BT received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. RH has no conflicts of interest to disclose. MK is an employee of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. ML has received honoraria from Quintiles, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Dignitana, Genentech, Foamix, Janssen R&D, Michael’s Mission, Novartis, Oncology Training International (OTI), and RP Pharmaceuticals. ML has received research funding from Berg, Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 1115 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tischer, B., Huber, R., Kraemer, M. et al. Dermatologic events from EGFR inhibitors: the issue of the missing patient voice. Support Care Cancer 25, 651–660 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3419-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3419-4