Abstract

Purpose

Bortezomib, a first-generation proteasome inhibitor, induces an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response, which ultimately leads to dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ and apoptotic cell death. This study investigated the role of the Ca2+-dependent enzyme, calpain, in bortezomib cytotoxicity. A novel therapeutic combination was evaluated in which HIV protease inhibitors were used to block calpain activity and enhance bortezomib cytotoxicity in myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Bortezomib-mediated cell death was examined using assays for apoptosis (Annexin V staining), total cell death (trypan blue exclusion), and growth inhibition (MTT). The effects of calpain on bortezomib-induced cytotoxicity were investigated using siRNA knockdown or pharmaceutical inhibitors. Enzyme activity assays and immunofluorescence analysis were used to identify mechanistic effects.

Results

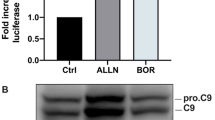

Inhibition of the Ca2+-dependent cysteine protease calpain, either by pharmacologic or genetic means, enhances or accelerates bortezomib-induced myeloma cell death. The increase in cell death is not associated with an increase in caspase activity, nor is there evidence of greater inhibition of proteasome activity, suggesting an alternate, calpain-regulated mechanism of bortezomib-induced cell death. Bortezomib initiates an autophagic response in myeloma cells associated with cell survival. Inhibition of calpain subverts the cytoprotective function of autophagy leading to increased bortezomib-mediated cell death. Combination therapy with bortezomib and the calpain-blocking HIV protease inhibitor, nelfinavir, reversed bortezomib resistance and induced near-complete tumor regressions in an SCID mouse xenograft model of myeloma.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams J, Palombella VJ, Sausville EA, Johnson J, Destree A, Lazarus DD, Maas J, Pien CS, Prakash S, Elliott PJ (1999) Proteasome inhibitors: a novel class of potent and effective antitumor agents. Cancer Res 59:2615–2622

Schenkein D (2002) Proteasome inhibitors in the treatment of B-cell malignancies. Clin Lymphoma 3:49–55

Kane RC, Bross PF, Farrell AT, Pazdur R (2003) Velcade: U.S. FDA approval for the treatment of multiple myeloma progressing on prior therapy. Oncologist 8:508–513

Landowski TH, Megli CJ, Nullmeyer KD, Lynch RM, Dorr RT (2005) Mitochondrial-mediated disregulation of Ca2+ is a critical determinant of Velcade (PS-341/bortezomib) cytotoxicity in myeloma cell lines. Cancer Res 65:3828–3836

Milani M, Rzymski T, Mellor HR, Pike L, Bottini A, Generali D, Harris AL (2009) The role of ATF4 stabilization and autophagy in resistance of breast cancer cells treated with Bortezomib. Cancer Res 69:4415–4423

David E, Kaufman JL, Flowers CR, Schafer-Hales K, Torre C, Chen J, Marcus AI, Sun SY, Boise LH, Lonial S (2010) Tipifarnib sensitizes cells to proteasome inhibition by blocking degradation of bortezomib-induced aggresomes. Blood 116:5285–5288

Hoang B, Benavides A, Shi Y, Frost P, Lichtenstein A (2009) Effect of autophagy on multiple myeloma cell viability. Mol Cancer Ther 8:1974–1984

Klionsky DJ (2007) Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:931–937

Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 40:280–293

Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E (2007) Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7(12):961–967

Oubrahim H, Chock PB, Stadtman ER (2002) Manganese(II) induces apoptotic cell death in NIH3T3 cells via a caspase-12-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 277:20135–20138

Tan Y, Wu C, De Veyra T, Greer PA (2006) Ubiquitous calpains promote both apoptosis and survival signals in response to different cell death stimuli. J Biol Chem 281:17689–17698

Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J (2003) The calpain system. Physiol Rev 83:731–801

Masters JR, Thomson JA, Daly-Burns B, Reid YA, Dirks WG, Packer P, Toji LH, Ohno T, Tanabe H, Arlett CF, Kelland LR, Harrison M, Virmani A, Ward TH, Ayres KL, Debenham PG (2001) Short tandem repeat profiling provides an international reference standard for human cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8012–8017

Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R, Tuschl T (2002) Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi. Cell 110:563–574

Biederbick A, Kern HF, Elsasser HP (1995) Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) is a specific in vivo marker for autophagic vacuoles. Eur J Cell Biol 66:3–14

Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11:36–42

Debnath J, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G (2005) Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy 1:66–74

Komatsu M, Ichimura Y (2010) Physiological significance of selective degradation of p62 by autophagy. FEBS Lett 584:1374–1378

Wan W, DePetrillo PB (2002) Ritonavir inhibition of calcium-activated neutral proteases. Biochem Pharmacol 63:1481–1484

Ghibelli L, Mengoni F, Lichtner M, Coppola S, De Nicola M, Bergamaschi A, Mastroianni C, Vullo V (2003) Anti-apoptotic effect of HIV protease inhibitors via direct inhibition of calpain. Biochem Pharmacol 66:1505–1512

Ding WX, Ni HM, Gao W, Yoshimori T, Stolz DB, Ron D, Yin XM (2007) Linking of autophagy to ubiquitin-proteasome system is important for the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell viability. Am J Pathol 171:513–524

Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K, Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K, Shiosaka S, Hammarback JA, Urano F, Imaizumi K (2006) Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol 26:9220–9231

Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S (2005) Another way to die: autophagic programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ 12(Suppl 2):1528–1534

Li H, Nepal RM, Martin A, Berger SA (2012) Induction of apoptosis in Emu-myc lymphoma cells in vitro and in vivo through calpain inhibition. Exp Hematol 40:548–563

Demarchi F, Bertoli C, Copetti T, Tanida I, Brancolini C, Eskelinen EL, Schneider C (2006) Calpain is required for macroautophagy in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 175:595–605

Madden DT, Egger L, Bredesen DE (2007) A calpain-like protease inhibits autophagic cell death. Autophagy 3:519–522

Evans JS, Turner MD (2007) Emerging functions of the calpain superfamily of cysteine proteases in neuroendocrine secretory pathways. J Neurochem 103:849–859

Grumelli C, Berghuis P, Pozzi D, Caleo M, Antonucci F, Bonanno G, Carmignoto G, Dobszay MB, Harkany T, Matteoli M, Verderio C (2008) Calpain activity contributes to the control of SNAP-25 levels in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 39:314–323

Foti C, Demarchi F, Brancolini C (2009) Inhibitors of the ubiquitin-proteasome system are not all alike: identification of a new necrotic pathway. Autophagy 5:543–545

Storr SJ, Carragher NO, Frame MC, Parr T, Martin SG (2011) The calpain system and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 11:364–374

Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, Shoemaker RH, Best CJ, Abu-Asab MS, Borojerdi J, Warfel NA, Gardner ER, Danish M, Hollander MC, Kawabata S, Tsokos M, Figg WD, Steeg PS, Dennis PA (2007) Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 13:5183–5194

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF), and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute [CA23074, CA017094]. Bortezomib (PS-341/Velcade®) was generously provided by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

280_2013_2156_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 1 CAPNS1 siRNA reduction of calpain expression and activity. 8226 myeloma cells were transduced with CAPNS1 siRNA expression constructs and selected under puromycin. (A) Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for calpain small subunit 1 protein expression. (F) Myeloma cell lines 8226/siCT and 8226/siCAPNS1 were lysed, and 100 µg of total protein was incubated with the fluorescent substrate Ac-LLY-AFC in the presence of Ca2+. Enzyme activity was read by fluorescence intensity and expressed as relative fluorescence units (RGF)/µg protein. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (PDF 27 kb)

280_2013_2156_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 2 (A) Quantitative analysis of acidic vesicle formation in myeloma cells. The 8226 myeloma cell line was incubated with 10 nM BZ or EBSS for 4 h, stained with monodansylcadaverine (MDC) and immobilized in Glycosan extracellular matrix on glass coverslips for fluorescent image analysis. (A) Mean number of vesicles per cell (mean + SEM. * p < 0.01, n = 40). (B) Mean vesicular-to-cytosolic ratio is the mean fluorescence intensity within the vesicles compared with cytosolic fluorescence within the same cell to normalize for differences in cell loading. (B) Relative expression of LC3II (A) and p62 (B) in 8226 myeloma cells. Pixel density of Western blot analysis (Fig 3B) was determined using Image J. Data shown are the mean of 3 independent experiments. (PDF 37 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Escalante, A.M., McGrath, R.T., Karolak, M.R. et al. Preventing the autophagic survival response by inhibition of calpain enhances the cytotoxic activity of bortezomib in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 71, 1567–1576 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-013-2156-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-013-2156-3